关键词 > COMP3331/9331

COMP3331/9331 Computer Networks and Applications Assignment for Term 2, 2023

发布时间:2023-08-01

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

COMP3331/9331 Computer Networks and Applications

Assignment for Term 2, 2023

Version 1.0

Due: 11:59am (noon) Friday, 28 July 2023 (Week 9)

1. Introduction

A DNS (Domain Name System) resolver is a crucial component in computer networking that translates human-readable domain names (like www.example.com) into corresponding IP addresses (such as 192.0.2.1). The DNS resolver performs the task of querying DNS servers to obtain the IP address associated with a given domain name. You are required to implement a DNS resolver that can resolve domain names to their corresponding IP addresses.

Initially, you will design and develop a basic version (worth 8 marks). Then, you will enhance the basic version with some additional features (worth the remaining 12 marks). In total this assignment is worth 20 marks.

2. Basic Version

You will develop two network applications:

1. Resolver: Your resolver will extract information from name servers in response to client requests. In the literature you may come across similar names which share common functionality, such as recursive resolver, recursive server, recursive name server, and full- service resolver.

2. Client: Your client will provide a command-line interface to allow users to generate queries, wait for aresponse, and display the results.

2.1 System Overview

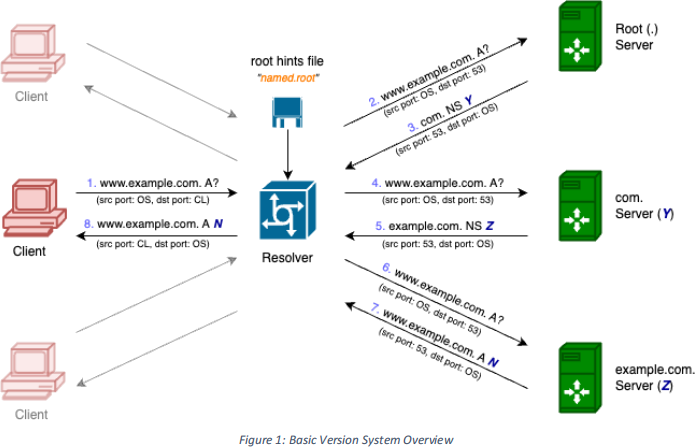

A high-level overview and an example of DNS resolution is provided in Figure 1. When the resolver is first executed it reads in a “root hints file” , which contains the names and IP addresses of the authoritative name servers for the root zone 1. This is necessary for the resolver to bootstrap the resolution process. The resolver will listen for queries on a UDP port which is specified as a command-line argument. Clients will send queries from a UDP port which is automatically allocated by the operating system. Upon receiving a query, the resolver will repeatedly make non-recursive queries, starting at the root and following referrals, to iteratively resolve the query on behalf of the client.

In the example of Figure 1, the client is querying to find the domain name to IP address mapping for “www.example.com”. That is, the type “A” resource record(s) associated with “www.example.com”.

The first transaction involves the query (step 1) from the client to the resolver. The resolver will only respond (step 8) once it has obtained the answer. This answer is a result of multiple queries to a number of authoritative DNS servers.

The resolver will typically resend the query (step 2) to one of the authoritative DNS servers for the root zone (“.”), which will respond (step 3) with the list of authoritative DNS servers for the “.com” zone.

The resolver will then resend the query (step 4) to one of the authoritative DNS servers for the “.com” zone, which will respond (step 5) with a list of authoritative DNS servers for the “example.com” zone.

Finally, the resolver will resend the query (step 6) to one of the authoritative DNS servers for the “example.com” zone, which will respond (step 7) with the answer to the original query. That is, a list of IP addresses (the single fictional “N” address in the figure) corresponding to the domain name “www.example.com”.

Note that in this example the resolver arrived at an authoritative answer. However, any of the queried servers may have had the requested records cached, in which case the resolution process may have terminated earlier with anon-authoritative answer.

2.2 Communications and the Client-Server Paradigm

You may assume all communication is over UDP/IPv4 and all DNS servers will use port 53, as highlighted in Figure 1.

You may also note from the figure that the client port is marked as “OS” . This is to indicate that it should be allocated automatically by the operating system. Meanwhile the resolver port for communicating with clients is marked as “CL” . This is to indicate that it should be specified as a command-line argument. This is because the client will need to initiate communication with the resolver, and therefore the resolver will need to be listening on a known port. The resolver in this situation is the “server” in the “client-server paradigm”. The resolver however does not need to know the client’sport in advance, as it will learn it upon receiving a query and store this information, along with the client’s IP address, to correctly address the response.

Conversely the resolver assumes the role of “client” for resolver-DNS communications. As such, the resolver does not need a known port to perform the query resolution, so it should be allocated automatically by the operating system. The name servers will learn the resolver port and IP address upon receiving a query, and similarly store this information to correctly address the response.

2.3 Client Operation

The client will be executed from the command-line. The client should minimally allow for the following command-line arguments:

• resolver_ip: the IP address of the host on which the resolver is running. If the client and resolver are running on the same host then this should be the loopback address, 127.0.0.1.

• resolver_port: the port on which the resolver is listening. This should match the port argument given to the resolver at run-time.

• name: the name of the resource record that is to be looked up.

Consider this example execution where the client is a C program:

|

$ ./client 127.0.0.1 5300 www.example.com |

The client should initiate a query for the type A record(s) for www.example.com. The query should be sent to the resolver at 127.0.0.1:5300.

The client should implement some basic argument validation. For example, that the necessary number of arguments are provided and that each has the correct domain. If the arguments are invalid then the client should terminate with a usage message, for example:

|

$ ./client Error: invalid arguments Usage: client resolver_ip resolver_port name |

This is not something that will be stress tested. It’s merely to provide improved usability and simplify the marking process should your client deviate from the expected interface, particularly if you implement any of the enhancements in Section 3 that require changes to the interface.

Once the arguments are validated the client should construct a DNS query for the given name. This will require a more in-depth understanding of the DNS message format. As a starting point, you should refer to “RFC- 1034 Domain Names – Concepts and Facilities”2 and “RFC- 1035 Domain Names – Implementation and Specification”3. You may assume that all queries will be standard queries4. A standard query specifies a target domain name, query type, and query class, and asks for resource records which match. You may also assume that all queries will be of type A and class IN. You should randomly generate an ID for the query. You should not indicate that recursion is desired, i.e. the query should be iterated. You will find more information on all these aspects in the RFC’s.

Once the query message is prepared it should be sent to the resolver address that was provided as command-line arguments. The client should then wait for a response. Upon receiving a response, the client should parse the message and display the results. You are free to nominate the output format, but minimally it should include the answers, whether (or not) those answers are authoritative, and whether the message was truncated. You may refer to similar tools such as nslookup and/or dig for inspiration as to how you may want to format the output.

Regarding truncation, in the original DNS specification, DNS messages carried by UDP were restricted to 512 bytes (not counting the IP or UDP headers). Longer messages were truncated, and the TC bit is set in the DNS message header5. You do not need to account for this any further than indicated above.

You do not need to account for any additional error conditions beyond your control, such as a network error, an unresponsive server, or that the queried name does not exist. You also do not need to account for internationalised domain names.

You may benefit from developing your client initially and independently of your resolver. This should allow you to test it against your local DNS, or a public DNS server67, and ensure you’re generating queries and parsing responses correctly. The relevant code may then be easily transferrable to your resolver, or factored out into a library, to be used by both applications.

During development you may also find it helpful to capture and inspect your DNS queries and their responses with Wireshark. Note this won’t be possible within CSE, however, as traffic recording is disabled.

2.4 Resolver Operation

The resolver will be executed from the command-line. The resolver should minimally allow for the following command-line argument:

• port: the port on which the resolver should listen for queries. This should match the port argument given to the client at run-time. It should be a value in the range 1024 – 65535.

Consider this example execution where the resolver is a C program:

|

$ ./resolver 5300 |

The resolver should bind to UDP port 5300 and listen for client queries.

The resolver should implement some basic argument validation. For example, that the necessary number of arguments are provided and that each has the correct domain. If the arguments are invalid then the client should terminate with a usage message, for example:

|

$ ./resolver Error: invalid arguments Usage: resolver port |

This is not something that will be stress tested. It’s merely to provide improved usability and simplify the marking process should your resolver deviate from the expected interface, particularly if you implement any enhancements in Section 3 that require changes to the interface.

Once the arguments are validated the resolver should first read in the root hints file, which contains resource records for the root name servers. This file named.root will be located in the working directory of the resolver. You do not need to account for the file being absent, having a different name, or being in a different format. In parsing the file, you may ignore lines that start with a semi- colon, which are comments, blank lines, and type AAAA records, which are for IPv6. A copy of the file is available with this specification but may also be downloaded from InterNIC8.

Once the file has been loaded by the resolver it should bind to the UDP port specified as a command- line argument and listen for queries. During testing the resolver and all clients will be executed on the same host. As such, it is only necessary for the resolver to bind to the loopback interface. You may,however, choose to (also) bind to the network interface such that clients may issue queries from other hosts on the local network.

Once the resolver receives a request it should initiate the resolution process. As a starting point, you should refer to the relevant sections of RFC- 10349 and RFC- 103510. Note that your resolver is a simplification of the algorithm detailed in those sections. For example, in this basic version your resolver only needs to deal with standard queries, of a single class (“IN”), and a single type (“A”). Additionally, in this basic version your resolver does not need to cache records, multiplex multiple requests, nor deal with a variety of error conditions.

The resolver is, however, expected to support multiple clients, but for the basic version it need not do so in parallel. It is sufficient for the resolver to process requests one at a time. Once again this will not be stress tested. During marking a handful of clients will be manually executed in separate terminals with some possible overlap.

You may also note that during testing the resolver will always be started before any client requests are made, the resolver will not be manually terminated, and should the resolver crash, it will be restarted.

As with your client, during development you may find it helpful to capture and inspect your DNS traffic with Wireshark.

3. Enhancements

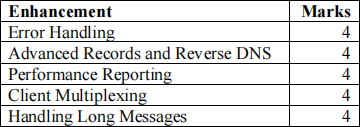

Once you have the basic resolver and client working you will implement a subset of up to 3 of the features detailed below.

As part of your submission, you will include a mark request. Within the mark request you will highlight the enhancements you’ve chosen to implement, any known limitations or issues, and any possible solution(s). Only the enhancements nominated in the mark request will be assessed.

Specifying details of known limitations or issues, and possible solutions, within your mark request may make you eligible to recover lost marks for the component. Up to 25% of the available marks maybe awarded when a reasonable and non-trivial description is provided. This further relies on you having made some non-trivial effort to implement the feature.

3.1 Error Handling (4 marks)

RFC- 1034 notes that resolvers typically spend much more logic dealing with errors of various sorts than with typical occurrences11. Neither the basic version of the resolver nor the client consider error conditions beyond user validation. Both applications should be enhanced to be responsive to both error codes and timeouts.

3.1.1 Error Codes

Each DNS message header contains a response code12. When non-zero this indicates some error condition. Expand both the resolver and the client to respond appropriately.

When the client receives a response indicating any of:

• format error

• server failure

• name error

The client should report a meaningful error message to the user and terminate. For example, consider aname error:

|

$ ./client 127.0.0.1 5300 www.xeample.com Error: server can't find www.xeample.com |

For all other error conditions, the client can simply report the error code.

Should the resolver receive a response indicating some error condition generally it should terminate the resolution process and forward the message to the client. One exception to this is server failure. In this case the resolver should exhaust its search space before reporting an error to the client.

For example, the resolver is bootstrapped with the addresses of the 13 logical root servers. Should a query to the first server result in server failure, then the resolver should re-issue the query to the second server, and soon, until it either receives a valid response or runs out of servers to query. You may wish to revisit the “Resolver internals” section of RFC- 103413 and the “Resolver Implementation” section of RFC- 103514 for further information and guidance, in particular the use of the SLIST data structure.

3.1.2 Timeouts

The resolver (and client) should also be robust against an unresponsive server (or resolver). The logic of both applications should be expanded to include a timeout period for queries. This will require modification of their interfaces, which should now accept an additional argument:

• timeout: the duration in seconds, greater than 0, which the client/resolver should wait for a response from the resolver/server, before considering it a failure.

Consider this example execution where the client is a C program:

|

$ ./client 127.0.0.1 5300 www.example.com 5 |

The client should initiate a query for the type A record(s) for www.example.com. The query should be sent to the resolver at 127.0.0.1:5300, and the client should wait up to 5 seconds for a response.

Argument validation should check that the timeout value is valid, and the usage message updated. For example:

|

$ ./client Error: invalid arguments Usage: client resolver_ip resolver_port name timeout |

You are also free to improve the interface. For example, you may nominate a default value of 5 seconds for the timeout, such that the user may elect to not specify this parameter. Such changes should however be reflected in your usage message, for example:

|

$ ./client Error: invalid arguments Usage: client resolver_ip resolver_port name [timeout=5] |

Please note the above doesn’t consider other enhancements that require interface modifications. Where multiple such enhancements are implemented, their interface modifications should be integrated appropriately and reflected in the usage message.

The same principles apply for the resolver interface.

When the client suffers a timeout it should simply report the timeout failure and terminate.

The resolver, however, should follow the logic noted previously for server failure errors, and exhaust its search space before reporting an error to the client.

3.2 Advanced Records and Reverse DNS (4 marks)

In addition to the type A of the basic version, implement MX, CNAME, NS, and PTR types. This will require modification of the client interface, which should now accept an additional argument:

• type: indicates what type of query is required. This should be case-insensitive, e.g. “ns”, “NS”, “nS”, and “Ns” should all be valid and treated equally.

Consider this example execution where the client is a C program:

|

$ ./client 127.0.0.1 5300 www.example.com NS |

The client should initiate a query for the type NS record(s) for www.example.com. The query should be sent to the resolver at 127.0.0.1:5300.

For PTR type queries, given an IP address, the resolver should return the corresponding domain name. This will require some additional parsing of the IP address by the client to put it in the correct form for the DNS query15.

Argument validation should check that the type is valid and supported, and the usage message updated. For example:

|

$ ./client Error: invalid arguments Usage: client resolver_ip resolver_port name type |

You are also free to improve the interface. For example, you may nominate a default value of A for the query type, such that the user may elect to not specify this parameter. Such changes should however be reflected in your usage message, for example:

|

$ ./client Error: invalid arguments Usage: client resolver_ip resolver_port name [type=A] |

Please note the above doesn’t consider other enhancements that require interface modifications. Where multiple such enhancements are implemented, their interface modifications should be integrated appropriately and reflected in the usage message.

3.3 Performance Reporting (4 marks)

Collect performance data for your resolver in terms of percentile 16 of resolving time and compare against at least two standard (public) resolvers, such as Google DNS17, 1.1.1.118, and/or OpenDNS19.

How you approach the data collection is flexible. For example, you might capture the resolution time at either the client or the resolver.

The client itself should natively support sending queries to any public resolver . It should simply be a case of specifying the appropriate command-line arguments for the resolver’s IP address and port.

If you’re capturing at the resolver, to conduct the experiments you might simply modify the bootstrapping process such that it doesn’t initiate queries at the root, but rather defers all queries to a particular public resolver.

You will then need a mechanism to calculate and record the resolution time for each query. Once again, you can nominate how to approach this task. For example, your application might store measurements in some persistent database or simply append them to a text file, for later processing.

Each experiment should involve a minimum of 5,000 resolvable queries, to provide some statistical significance. Each resolver should be tasked to resolve the same batch of queries. This will benefit greatly from some form of automation. For example, once the client and/or resolver are configured to capture statistics, and a file of target domain names is prepared, a script may be run which reads from the file and calls the client with each query.

Ideally the distribution of queried domain names would follow some sort of inverse power law, i.e. few domains are the target of most queries, and most domains are the target of few queries. You may search the Internet for existing lists of domain names.

Your submission must additionally include a file performance.pdf that includes:

• A brief description of how you conducted the experiment.

• A brief description of how the experiment can be repeated.

• The results presented in tabular form.

• The results presented in graphical form.

This document need only be 1-2 pages long.

To make data collection more efficient, you may wish to consider also implementing the client multiplexing enhancement.

3.4 Client Multiplexing (4 marks)

The resolver must be able to multiplex multiple requests if it is to perform its function efficiently. The resolution process is I/O intensive, and rather than block while servicing individual requests, it should employ some mechanism to service multiple requests concurrently.

A robust way to achieve this is to use multithreading. In this approach, you will need a main thread to listen for new requests. For each client request, you will need to create a new thread. Note that, you will need to define appropriate data structures for managing the state of each request. While we do not mandate the specifics, it is critical that you invest sometime into thinking about the design of your data structures. Some examples of state information provided in RFC- 103520 include a timestamp indicating the time the request began, and some sort of parameters to limit the amount of work which will be performed for the request. You may also find it useful to record such things as the query ID and the client address. You cannot assume a fixed number of requests upfront for defining data structures. As you may have learnt in your programming courses, it is not good practice to arbitrarily assume a fixed upper limit on such things. Thus, we strongly recommend allocating memory dynamically for all the data structures that are required. Once the processing of a request is considered complete the corresponding thread should be terminated. You should be particularly careful about how multiple threads will interact with any shared data structures. Code snippets for multi-threading in all supported languages are available on the course webpage.

Another approach could be to use non-blocking or asynchronous I/O by using polling, i.e., select(). The resolver would have a single thread of execution where it continuously checks for newly arrived packets to process.

No particular approach is mandated, but testing will involve additional stress beyond that described in the basic version. For example, rather than manually interfacing with a small number of clients to generate requests sequentially, a script may be employed to generate a larger number of requests concurrently.

3.5 Handling Long Messages (4 marks)

As was noted in Section 2.3, historically DNS messages carried by UDP are restricted to 512 bytes21. This was to ensure that messages wouldn’t be fragmented at the network layer. Messages exceeding this size are truncated and the TC bit is set in the DNS header.

To overcome this limitation, the resolver can establish a TCP connection with the server andre-issue the query. Messages sent over TCP connections also use server port 53.

TCP does, however, come at a performance cost. To reduce reliance on TCP, RFC-689122 specified Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS). In particular, a server can advertise a larger response size capability, which is intended to help avoid truncated UDP responses, which in turn cause retry over TCP.

To provide robust and performant support for longer messages, the resolver should implement both of these features. When necessary, the resolver should fallback to TCP, and where possible, the resolver should negotiate the use of EDNS. The client must additionally output the size of the received DNS message.

4. References

In addition to the resources provided as footnotes, you may find valuable information contained in the following RFC’s. Please note this list is by no means exhaustive, and the relevance of some of these maybe quite minimal (e.g. RFC-2821 may only be relevant in resolving MX type queries). RFC- 1034 and RFC- 1035 will likely be your primary source of information.

• [RFC1033] Domain Administrators Operations Guide

• [RFC1034] Domain Names - Concepts and Facilities

• [RFC1035] Domain Names - Implementation and Specification

• [RFC1123] Requirements for Internet Hosts - Application and Support

• [RFC2181] Clarifications to the DNS Specification

• [RFC2308] Negative Caching of DNS Queries (DNS NCACHE)

• [RFC2821] Simple Mail Transfer Protocol

• [RFC4343] Domain Name System (DNS) Case Insensitivity Clarification • [RFC6891] Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS(0))