Lab Exercises for COMP26020 Part 2: Functional Programming in Haskell

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

Lab Exercises for COMP26020 Part 2: Functional Programming in Haskell

This lab has three exercises, for a total of ten marks. The first two exercises together are worth eight marks, and I advise all students to focus exclusively on these exercises. Seven marks are given based on automated testing, and one is reserved for human judgement by the marker. These exercises are described in Section 1 below.

If you are certain that your solutions are completely correct you might like to look at Section 2 below, which describes a challenge exercise worth two marks. It is designed to be extremely difficult, and is not a practical way of gaining marks!

1 Simple Quadtrees

This lab exercise concerns as data structure called a ‘quadtree’ which can be used to represent an image. There are sophisticated versions of the quadtree data structure, but for the purposes of the lab we will use a very simple version of the idea.

Suppose we want to represent a square, black and white bitmap image which is 2n by 2n pixels. The usual way to do this is as a 2n by 2n grid of bits, but this can be wasteful if there are large monochrome areas.

In that case, a simple optimization is to think of the image as split into four sub-images:

One consisting of the pixels with co-ordinates less than or equal to those of the middle pixel on both axes of the image,

one consisting of the pixels with co-ordinates less than or equal to those of the middle pixel on the first axis but greater than those of the middle pixel on the second axis,

one consisting of the pixels with co-ordinates greater than those of the middle pixel on the first axis but less than or equal to those of the middle pixel on the second axis, and

one consisting of the pixels with co-ordinates greater than those of the middle pixel on both axes.

To fix our terminology, we call the first of these the “first quadrant”.1 If the sub-image is all one colour, we can represent this by one bit of information.

But if it contains different colours, we can subdivide again, and keep going recursively until we do get sub-images which are only one colour. (This definitely happens once we get down to the scale of the original pixels!). We call these

single colour sub-images in the final data structure ‘cells’.

This lab exercise is about the resulting data structure, the tree of cells. You don’t have to care about the details of an original image which such a structure might have come from – for instance you don’t need to record the dimensions in pixels of the original image, nor do you need to worry about whether a particular structure is the most efficient way of representing a given image. That means that your data structure is correct if it represents the way the image looks geometrically, ignoring the size. It will be tested in such a way that only the geometric information matters: the way you think about the data structure could differ from someone else by rotation, scaling, and even reflection, as well as the details of how you order and organize the various components, and you can both be correct as long as you are each internally self-consistent.

For that reason, if you are working out what the exercises mean with a friend, or on asking something on the forum, it is better to discuss everything in terms of pictures, or describe quadtrees using the four functions in Exercise 1 below, so that you don’t accidentally discuss the details of your data structure.

1.1 Exercise 1: representing quadtrees using ADTs

For this exercise, you should define an Algebraic Data Type to model quadtrees in the sense described above. Do this in whatever way you like (as long as you use an Algebraic Data Type), but provide four functions with the following properties:

● A function allBlack which takes an Int number2 n, which you may assume is of the form 2k where 亿 is non-negative, and returns your repre- sentation of an n by n image which is all black. (You have some freedom in how you interpret this – see the last paragraph of the section above! In particular this may be extremely simple because of the fact that you don’t need to remember the dimensions of the image. But it doesn’t have

to be simple if you find it helpful to represent the image more concretely.)

2 If you started working using the lab preview, and have assumed an argument of type ‘Integer’ instead of ‘Int’ that is fine too.

A function allWhite which takes an Int number n, which you may assume is of the form 2k where 亿 is non-negative, and returns your representation of an n by n image which is all white.

A function clockwise which takes four quadtrees and returns the quadtree whose four subtrees are the inputs, starting with the one in the first quad- rant and arranged in a clockwise order. (Again, there is freedom in how you arrange your data structure. It doesn’t matter how the subtrees are stored or ordered internally.)

● A function anticlockwise which takes four quadtrees and returns the quadtree whose four subtrees are the inputs, starting with the one in the first quadrant and arranged in a anticlockwise order.

You may use one or several Algebraic Data Types in your model. For each Algebraic Data Type, you should add the expression derviving (Eq, Show) to the end of the line which defines the datatype.

For example, below is an Algebraic Data Type representing a list of Int values

data MyList = Elist |

Cons Int MyList

If I used such a data structure in my solution, I would append the expression above to the end of the definition, to obtain

data MyList = Elist |

Cons Int MyList deriving (Eq, Show)

Make sure you have done this for all the Algebraic Data Types you have defined. For now we treat this as a ‘magic incantation’ which lets Haskell know we want to be able to print values of our datatype and compare them for equality.

What is really going on in this expression will be covered in the videos in Week 11.

Marking

This exercise is has a total of three marks available. The marks will be assigned based on testing on quadtrees of different sizes and complexities; more detail will be given in the final version of the lab instructions.

The tests will consist of checking consistency properties which we expect to hold. For example, we expect

clockwise (allBlack 1) (allBlack 1) (allWhite 1) (allWhite 1) == anticlockwise (allBlack 1) (allWhite 1) (allWhite 1) (allBlack 1)

The tests will also involve checking inequalities such as

clockwise (allBlack 1) (allBlack 1) (allWhite 1) (allWhite 1) /= anticlockwise (allBlack 1) (allBlack 1) (allWhite 1) (allBlack 1)

Otherwise you could represent all trees with a single value! Note however that they do not check anything which depends on the size of the image, so for instance they never check whether allBlack 128 == allBlack 2 or not, be- cause geometrically these look the same, so you are free to represent them as the same or different, whichever works for your data structure. The tests only check equalities and inequalities which must hold for all correct representations.

You solution will receive:

● One mark for passing the tests on small quadtrees,

● One mark for passing the tests on medium-sized quadtrees, and

● One mark for passing the tests on large quadtrees,

for a total of three marks. The quadtrees involved no larger than required to represent a 210 by 210 image. The ‘small’ quadtrees are no larger than needed to represent a 4 by 4 image. You need only consider square images whose dimensions are powers of 2. Your solution must use at least one Algebraic Data Type to qualify for any of the marks above.

1.2 Exercise 2: A crude ‘edge detector’

For this exercise, you should define a function ndiff which takes a quadtree as input and returns a quadtree as output. It should not change the structure of the quadtree, but it should change the data representing the black and white colours in the following way. A cell of ndiff q should be black if and only if the corresponding cell of q was a different colour to any of the cells which touch it either along an edge or at a corner. You can think of such a function as an extremely crude approximation to an edge detector, although it is not practical to use it for that purpose!

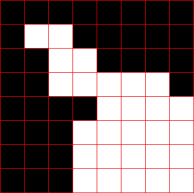

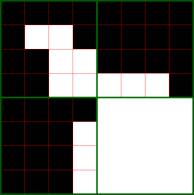

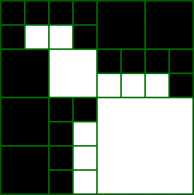

For example

Not that most of the cells have turned black, because they did differ from one of their neighbours – in some cases only a neighbour which touches on the corner.

Most cells have eight neighbours. However, a pair of cells in opposite corners are white, because the corresponding cells were black and only touched black cells. Note that these cells have fewer neighbours because of being on the boundary, which makes it more likely that they will be white in the output. (Though in this example, all the other cells on the boundary still had a neighbour of a different colour.)

Marking

This exercise is has a total of four marks available. The marks will be assigned based on testing on quadtrees of different sizes and complexities; more detail will be given in the final version of the lab instructions.

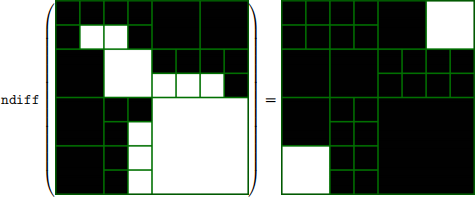

The tests will consist of checking properties which we expect to hold. For example,

ndiff (clockwise (allWhite 2)

(clockwise (allBlack 1) (allWhite 1)

(allWhite 1) (allWhite 1))

(allWhite 2) (allWhite 2)) ==

clockwise (allBlack 2)

(clockwise (allBlack 1) (allBlack 1)

(allBlack 1) (allBlack 1))

(allWhite 2) (allWhite 2)

You solution will receive:

One mark for passing the tests on small quadtrees,

One mark for passing the tests on medium-size, uniform quadtrees, and One mark for passing the tests on medum-size, non-uniform quadtrees,

One mark for passing the tests on large, non-uniform quadtrees,

for a total of four marks. The maximum size is the same as for Exercise 1. By ‘uniform’ I mean that the way in which the tree is described by clockwise, anticlockwise, allBlack, and allWhite does not intrinsically result in cells of different sizes being next to each other, though your data structure might introduce these if you like!

There is also one additional mark available for the first two exercises accord- ing to the marker’s judgement. It is for any good aspects of your code which are not reflected in the automated mark. This will generally be for extremely clear, well-organised code, or clever ideas for the efficiency of ndiff. The effi- ciency of your representation of quadtrees will never count against you, as you have complete freedom there. But it may be given for other good work if the marker feels, according to their judgement, that it is not reflected fairly in the automated mark.

2 Submission

To submit the exercises above, clone the git repository 26020-lab3-s-haskell_<your username> present in the department’s GitLab.

In that directory, save your submission as submission.hs and make sure you have done git add sumission.hs. Remove any definition of main from submission.hs.

A testing script is provided called check_submission.sh (note ‘sh’ not ‘hs’ !). Running this file checks that your submission will work with the au- tomated marking script. Note that it creates/overwrites a file called check_submission_temp_file.hs by concatenating submission.hs and tester.hs. It does not remove this file after running, so you can inspect it if anything went wrong. This script checks that your solution is in the right format for the au- tomated tests (e.g. that you have used the right function names, added the deriving (Eq, Show) incantation where necessary, and have remembered to remove any definition of main) but it does not test your submission well. Try to come up with your own test examples, although I will release some more examples on Blackboard too.

You might have to make check_submission.sh executable by running chmod u+x check_submission.sh.

Once check_submission.sh tells you that all its checks have passed, double check that you have added submission.hs and push the files on the master branch.

If you decide to try the challenge below and think you have succeeded in getting one of the marks, add your work to the repo as challenge.hs. Students are strongly encouraged to focus on the exercises above.

Once you are confident that your solution is correct (i.e. after doing more testing than just running the format checking script!), push your final version on the master branch and create a tag named lab3-submission to indicate that the submission is ready to be marked.

3 A Challenge

The exercises described in this section are designed to be extremely difficult: no amount of time spent on them is guaranteed to result in gaining marks, and they are best attempted only if the challenge in itself is sufficient motivation. I have told the TAs that they do not need to prepare to support these exercises, so you may need to ask me directly about any questions you have!

For the purpose of this exercise, an infinite bitstring is a function of type Integer -> Bool which does not go wrong in any way for any input which itself does not go wrong. We ignore how these functions behave on negative arguments, and think of them as functions on the natural numbers.

A total predicate is a function of type (Integer -> Bool) -> Bool which, given any infinite bitstring as input, terminates and outputs an element of Bool.

Your task is to implement a function

hero:: ((Integer -> Bool) -> Bool) -> (int -> Bool)

which given a total predicate p as input, outputs an infinite bitstring such that p(hero p) == True if and only if there exists an infinite bitstring e such that p(e) == True. Otherwise we must have p(hero p) == False if there are no such infinite bitstrings. Document how your solution works in your own words. A correct, well-documented solution is worth one mark.

A follow up problem is this: Does the idea which makes the solution to the above challenge work apply to total functions of type (Q -> Bool) -> Bool where Q is your quadtree datatype? If so, give an implementation for that type. if not, give an example of such a function for which the idea would not work, and clearly explain why in the comments. A well-reasoned solution is worth one mark.

4 Acknowledgements

I would like to thank everyone who asked questions about the preview version of these lab exercises. Particular thanks is due to Ewan Massey, who sent detailed feedback, including pointing out a serious problem (I had neglected to mention the deriving (Eq, Show) as a ‘magic incantation’ in the Week 9 videos! As mentioned above it’s meaning will be explained in Week 11). His feedback has saved all of us a lot of pain, and me a great deal of embarrassment!

2021-11-29