CS3214 Spring 2024 Exercise 1

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

CS3214 Spring 2024

Exercise 1

Due: See website for due date.

What to submit: A tar file that should contain the file answers.txt, which must be an UTF-8 encoded text file with answers for questions 1 and 2. For question 3, which asks for code, include a file named dpipe.c in your tar file.

Use the submit.py script in ~cs3214/bin/submit.py to submit your tar file from the command line, or use the submit website. Use the target identifier ‘ex1.’

The assignment will be graded on the rlogin cluster, so your answers must match this environment. In addition, every student will use a variant of dpipe that is unique to them; please visit cs3214/spring2024/exercises/exercise1to find the number of your variant.

Understanding Processes and Pipes

In this exercise we consider a program ‘dpipe,’ which, in connection with a ‘netcat’ utility program, can be used to turn any ordinary program into a network server. A ‘netcat’ utility program is a program that extends the standard Unix ‘cat‘ utility over a network.

The learning goals of this exercise are:

• Understand how to write C code that makes system calls.

• Understand how to start and wait for processes in Unix with the fork() and waitpid() system calls.

• Understand how to create pipes as an example of an IPC (interprocess communica- tion) facility.

• Understand how to manipulate a process’s standard input and standard output file streams using standard Unix system call facilities (e.g. dup2()) that affect low-level file descriptors. A very similar file descriptor manipulation is performed by a shell

when it sets up I/O redirection or pipes.

• Understand how to use the strace facility to trace a process’s system calls.

• Understand how to use the /proc file system to obtain information about processes in a system.

• Gain a deeper understanding of process states using a practical example application that combines process management, IPC, and network I/O.

In this exercise, you are asked to observe, reverse-engineer, and then reimplement the dpipe program. The dpipe binary is provided in ~cs3214/bin/dpipe.variants/ dpipe-ABC on our machines, where ABC is the unique id created for you. For netcat, use the ~cs3214/bin/gnetcat6 binary.

To allow you to invoke those commands directly, make sure that ~cs3214/bin and (optionally) ~cs3214/bin/dpipe.variants are included in your PATH environment variable. You should already have your PATH set up from exercise 0 to include the first directory. If you haven’t, do this now.

Here’s an example session of how to use it. Say you’re logged in to the machine ‘locust’ and run the command dpipe-ABC wc gnetcat6 -l 15999. This will produce out- put as follows:

[cs3214@locust sys1]$ ~cs3214/bin/dpipe.variants/dpipe-ABC wc gnetcat6 -l 15999 Starting: wc

Starting: gnetcat6

Running in server mode

Note that the shell is still waiting fordpipe to complete at this point. The questions listed in part 1must be answered at this point, after you have started dpipe, but before the next step. You may wish to continue reading and then return to this point, after opening a second terminal on the same machine.

The next command can be run on any rlogin machine, but you must replace locust with the name of the machine on which started the earlier command:

[cs3214@chinkapin ~]$ gnetcat6 locust-rlogin.cs.vt.edu 15999 < /etc/passwd Running in client mode

47 119 2690

[cs3214@chinkapin ~]$

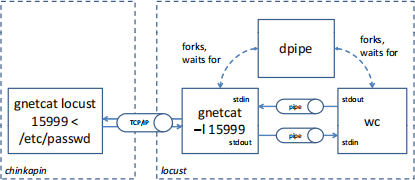

The gnetcat6 instance started here connected to the gnetcat6 instance running on locust, and sent its input there (in this case, the content of file /etc/passwd). Gnetcat (running on locust) outputs this data to its standard output stream, which is connected via a pipe to the standard input stream of the ‘wc’ program. The standard output stream of ‘wc’ is connected to the standard input stream of locust’s gnetcat6 instance. Anything out- put by ‘wc’ will then be forwarded to chinkapin’s gnetcat6 instance, which outputs it to its standard output, thus appearing on the user’s terminal on chinkapin. You have just turned the ordinary ‘wc’ program into a network service! The entire scenario is shown in Figure 1.

Finally, dpipe exits when both of the processes it started have terminated:

[cs3214@locust sys1]$

1. Using /proc The /proc file system, originally introduced as part of the Solaris OS, is a mechanism by which the Linux kernel provides information about processes

Figure 1: Using dpipe to cross-link two programs’ standard input and output streams.

to users. This information is organized in directories and files that can be accessed using ordinary tools such as ls or cat. However, they do not represent actual directories or files – rather, their content is created dynamically when a user accesses them, based on the current state of the system and its processes. The kernel creates a directory for each process, which is named for its pid. Within the directory, there are additional files and directories that describe the current state of the process.

After you have started dpipe with ‘wc’ and ‘gnetcat -l ...’, use the ps(1) command to find the process ids of these three processes, then use ps or /proc to find the parent process id, the process group id, and the current status of these processes.

(a) Provide the following information in table form:

|

Process |

PID |

Parent PID |

Process Group ID |

State |

|

dpipe-ABC |

|

|

|

|

|

wc |

|

|

|

|

|

gnetcat |

|

|

|

|

You may find the proc(5) man page useful.

Use the single letter Linux shorthand for the process state. (Omit additional identi- fiers such as s or + you may see.)

(b) You should find that all three processes are in the same state. To which of the 3 states of the simplified process state diagram discussed in lecture does this state correspond?

(c) Now examine the /proc/nnnnn/fd directories for each process. Use ls -l. For each process’s open file descriptors, enter in the table below the device or object to which it refers. Enter N/Oif a file descriptor is not currently in use.

|

File Descriptor |

dpipe-ABC |

wc |

gnetcat6 |

|

(stdin) 0 |

|

|

|

|

(stdout) 1 |

|

|

|

|

(stderr) 2 |

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

Look at Figure 1 and convince yourself that dpipe indeed creates the arrangement shown there (minus the network connection, which has not yet been created).

2. Using strace. Processes use system calls to obtain services from the kernel. The program ‘strace’ is a utility that can display which system calls a process is exe- cuting. strace can trace individual processes from start to end; on request, it can trace child and ancestor processes as well, and it can even trace already running processes. Familiarize yourselves with the ‘strace’ command (use ’man strace’, for instance). Frequently used switches include -f, -e, -p, -ff, and -o which you should memorize.

Run dpipe-ABC under strace, creating again the constellation of processes described in the introduction (wc and gnetcat6), and use gnetcat6 on another machine to send data until dpipe exits. Use the -ff and -o switches to strace to obtain separate listings fordpipe and its child processes.

(a) Identify which system calls the dpipe process made. From the relevant strace output, copy the entries corresponding to the system calls pipe2(), close(), fork(), waitpid(), and exit().

Hint: Linux’s implementation of the fork() system call is actually called clone(), waitpid() is implemented using wait4(), and exit() corresponds to exit_group().

pipe2 is a GNU extension that is not part of POSIX. It acts like pipe, except that it also provides the option to set flags on the file descriptors pipe returns.

(b) Identify some of the system calls the process executing ‘wc’ made. Select the entries corresponding to write(), dup2(), close(), and execve(). Stop at the first execve() call that was successful (listed as returning 0 in strace’s output.) The following system calls will be specific to the program dpipe started so they are not actually part of dpipe (recall that exec() replaces the current program, but continues the current process and thus continues the strace of that process.

(c) Like part b), except for the process executing ‘gnetcat6’ .

Note that the traces for part (b) and (c) correspond to the system calls made by the child processes spawned by dpipe-ABC between fork() and exec().

(d) Now, rerun strace with the switches -f -e wait4,accept,read without connecting the gnetcat6 client (like in part 1). All three processes will be inside the kernel, in one of these three system calls. Answer the following questions for each process:

• What is the state for each process, using the nomenclature of the simplified process state diagram discussed in lecture?

• Which process is in which system call?

• How can each process’s state be explained from the semantics of that system call?

Use the following example format for your answer: Process ‘dpipe’ is in the (insert state here) state in the (insert system call here) system call because it is (describe what caused it to be in this state).

If you are uncertain about the semantics of any of these system calls, be sure to read their man pages or ask on the discussion forum.

3. Implement dpipe-ABC.

Armed with the knowledge gained in the previous part, implement dpipe-ABC so that it issues exactly the system calls you’ve observed in the traces, in the same order.

In general, you should be looking for C functions with the same name as the system calls that appears in the strace. You may have noticed the C-like syntax in the strace output. However, for some system calls, you should instead use a POSIX function that wraps the actual system call. Notably, we recommend that you use fork() instead of calling clone(2) and waitpid() instead of wait4.

Although the OS will use predictable file descriptors in pipe2(), your program should use variables and not constants, e.g. calling close(3) would not be an acceptable solution.

Use the execvp() frontend for the execve() system call. Make sure you imple- ment argument passing correctly. dpipe should first invoke the program whose name is given as its first argument, without passing any additional arguments to it. Then it should interpret the second argument as the name of a second program and pass the third argument as the first argument to the second program, the fourth argument as the second, and so on. It is customary to set argv[0] to the name of the program itself, and your invocations of execvp() should do the same. Hint: it is possible to achieve this without creating a complete copy of the argv[] ar- ray passed todpipe’s main program by crafting a NULL-terminated subarray with careful pointer manipulation.

If done correctly, the strace output for the relevant system calls 6 in your dpipe- ABC implementation must be identical to the output obtained from the provided dpipe-ABC; in fact, this is what the autograder software will check. Note that the autograder will use examples other thangnetcat6.

Important: even though the relative order of some of the system calls is not impor- tant for the correct functioning of dpipe, your assigned variant of dpipe will have a specific ordering your submission must reproduce to obtain full credit.

Make sure that your dpipe-ABC does not return to the prompt prematurely, or fails to return to the prompt after its children have exited.

Important: We will use the compiler switches -O -Wall -Werror when compil- ing your program. If you compile without these switches, and any warnings occur in your code, you run the risk of failing our autograding scripts.

2024-01-30