Econ 266 Financial Markets & Institutions Final Exam

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

Financial Markets & Institutions (Econ 266)

Final Exam Sample Questions

1) What is one advantage and one disadvantage of private over public

equity from the perspective of the issuer? How about from the perspective of the investor?

By closely managing the running of the businesses they own,

private equity can reduce the principal-agent problem that can

hamper public equity (where the owners are less able to monitor the performance of those they hire to manage the firm). But it is often easier to raise more money in public markets, which are

open to a wider swath of investors. For investors, private equity can often offer better returns, but tend to be riskier, in part b/c they use more leverage, and less liquid, requiring investors to tie up their money for longer periods.

2) a)Why does the price of an existing bond decline when interest rates rise, and why is this decline greater for bonds of longer maturity?

If interest rates rise, the coupon rate on existing bonds becomes

less attractive relative to the higher rates available on new bonds, so the price of existing bonds will fall, until its rate of return from this lower price equals the higher rates available on new bonds.

Equivalently, the future cash flows of existing bonds will be

discounted at the higher interest rate that’s available on new

bonds. Since bonds with longer maturities have more future cash flows to discount, the rise in the discount rate will cause a bigger

drop in their price than in the price of bonds of shorter maturities.

b) “If nominal interest rates decline, the value of equities increases.” Do you agree?

Not necessarily. If the decline in nominal interest rates is caused entirely by a fall in inflation expectations, it won’t have much

impact on equity valuations, b/c although the rate used to discount future free corporate cash flows will fall, so too will the expected

nominal growth of those cash flows (b/c oflower inflation

expectations). By contrast, if the decline in nominal rates owes

entirely to a fall in real rates, only the discount rate will decline, and the value of equities will hence rise.

c) Suppose an investor buys an asset at a price of $50, using 50% leverage. The asset pays a return of 4% at an annual rate (in equal

quarterly installments). Borrowing costs are 5% at an annual rate. If

the investor sells the asset after 3 months and earns a holding period

return (HPR) of 12.75% (not annualized), what was the sale price of the asset?

HPR = .1275 = {P + (.04/4) 50} – {25 + 25(1+(.05/4))}

25

where P = sale price of the asset. Divide annual rates by 4 b/c asset was held for 3 months. Asset was bought at $50 w/50% leverage, so investor put up $25 in cash and borrowed $25 (at 5% interest). So P = 53

3) Suppose that a CDO is comprised of four underlying loans, each with a face value of $100m. The CDO pays no coupons. The CDO is sold at a discount to face value in three tranches: senior tranche (face value of $200m), mezzanine tranche ($100m), and junior tranche ($100m).

a) Will the price paid for the senior tranche be higher, lower, or the same if the probabilities of default of the underlying loans are

correlated (compared to the case in which they are independent)?

If the probabilities of default of the loans are correlated (i.e., if one

loan defaults, the others are more likely to default too), the senior tranche offers less protection compared to the case in which the

default probabilities are independent, so the price paid will be lower.

b) If one of the underlying loans defaults with no recovery, one defaults with 50% recovery, and the other two payoff in full, how much will

each tranche receive?

There will be a total of $250m to pay out ($100m each for the two loans that pay in full, and $50m from the loan that defaults

with 50% recovery). The senior tranche will be paid first, in full

($200m), leaving $50m to be paid to the next (mezzanine) tranche. The junior tranche gets nothing.

4) a)Briefly explain whether you agree with the following statement: “ Derivatives are risky. “

Not necessarily. While certain derivatives can be used to take on risk, others can be used to hedge risk, to transfer it from those

wishing to avoid risk to others wishing to assume risk.

b) If the spot price of oil in six months time ends up differing from the current six-month future price for oil, would that be evidence against the efficient market hypothesis (EMH)?

No. EMH means that market prices reflect all currently available information, so that those prices are impossible to predict using

that information. It does not mean that markets are clairvoyant.

The spot price of oil in six months may differ from the current six- month futures price because new information becomes available that was not known at the time the current futures price was set.

5a) Briefly explain the maturity transformation role performed by banks, and what type of interest rate risk banks are exposed to as a result of that role.

Banks make long-term, illiquid loans, and fund them with short- term, liquid deposits. By doing this maturity transformation,

banks are matching the desires of deficit units (who want to

borrow long-term) with the desires of surplus units (who want

liquidity). But doing so exposes banks to the risk that short-term interest rates could rise relative to the long-term, fixed rates

outstanding on their loans, requiring them to pay more interest on their deposits, narrowing their net interest margin.

b) Suppose a bank wants to hedge that risk by entering into an interest rate swap. If the swap were for a six-month period, on a notional

principal of $200 million, and the fixed-rate component of the swap was 3% (annual rate), the floating rate 3.5% (annual rate), would the bank on balance receive money from the swap or pay – and how much?

To hedge that risk, the bank could enter into an interest rate swap where it pays fixed and receives floating. That way, if short-term rates rise, they will get paid on their swap, offsetting the

compression of their net interest margin. In this example, the bank would receive: (.035 - .03)*200m/2 = $0.5m (have to divide annual rates of interest by 2 b/c the swap is only for six months).

6) Suppose the spot price of the S&P 500 index is 4000, the dividend

yield on the stocks in the index is 2% (at an annual rate), and the cost of borrowing is 4% (at an annual rate).

a) If spot-future parity holds, what is the price of a six-month future on the S&P 500?

F = S (1+r/2 – d/2)

F = 4000(1+.04/2 - .02/2)

F = 4040

where r is borrowing rate, and d is the dividend rate; divide by 2 b/c it’s a six-month futures contract.

b) Suppose the future price is actually 30 more than consistent with

spot-future parity. What would investors do, what would be the profit from doing so, and how would their actions help restore spot-future

parity?

IfF = 4070 (i.e., futures are 30 above what would be consistent with spot-future parity), investors would sell the futures, and borrow (at 4% interest) to buy in the spot market at 4000 (and receive the 2% annual dividend for holding the S&P for six

months). That would result in a profit at the end of six months of: 4070 + (.02/2)*4000 – 4000(1+(.04/2)) = 30

Buying spot and selling futures will drive up the spot price and

drive down the futures price, helping restore spot-futures parity.

c) Consider two asset classes, A and B. Over the past 10 years, their returns have exhibited the same Sharpe ratio of 1.3, but A’s average return of 15% per year exceeds B’sreturn of 8% per year. If the risk- free rate has averaged 4% over the decade, what have been the

standard deviations of A and B’s returns? Which asset class is more likely to be venture capital as opposed to publicly traded equity?

SRi = (Ri – Rrf)/SDi where SRi, Ri, and SDi are the Sharpe Ratio,

return, and standard deviation of return, respectively for asset i, and Rrf is the risk-free return.

Asset A: 1.3 = (.15-.04)/SDA;Asset B: 1.3 = (.08-.04)/SDB; So SDA = .085; SDB = .031

Venture capital tends to offer higher returns but with more risk,

reflected in greater volatility of returns than publicly traded equities, so that likely corresponds to Asset A.

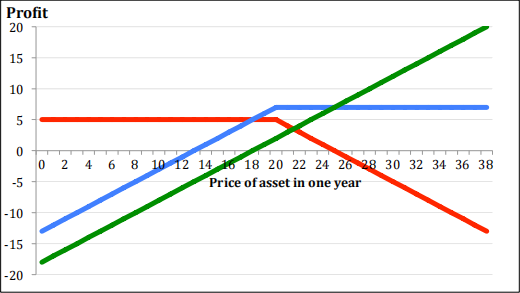

7) Consider three investors:

A: buys an asset at 18 and holds if for one year.

B: buys the same asset at 18 and also sells a call option on the asset with astrike of 20, for a price of 5, with an expiration in one year.

C: sells the same call option as B, but on an assethe doesn’town.

The chart below shows the profits of the three investors, as a function of the price of the asset in one year. Match the profit line to the investors.

Of the three, who likely thinks the asset is most apt to rise in price? Who thinks it is most likely to decline in price?

The green line is A, the blue line B, the red line C.

A likely thinks the asset is most apt to rise in price – that’s why A owns the asset outright, w/o selling a call option, and will benefit most if the asset rises in price. C is most apt to think the asset will

decline in price – that’s why C sells an uncovered call, which will profit if the asset declines in price.

8a) Consider two countries, A and B. Suppose the spot exchange rate is 1A = 1.2B, the one-year forward exchange rate is 1A = 1.18B, and one- year interest rates are 3.0% in country A. If covered interest parity

(CIP) holds, what is the one-year interest rate in country B?

1.03 = 1.2*(1+NB)/1.18, where NB is the interest rate in country B So NB = 1.3% (interest rate in B is ≈1.7% below the rate in A, b/c the forward rate builds in ≈1.7% appreciation of B’s currency).

b) Suppose the interest rate in country B was one percentage point

lower than consistent with CIP. What would an investor in country B do, and what would their profit be from doing so?

If NB = 0.3% (i.e., 1% lower than consistent with CIP), investor in B would borrow at that 0.3%, switch into A’s currency at the spot

rate, invest at 3% in A, and lock in the forward exchange rate at which those earnings can be brought back into B. This will result in a profit of:

(1.03/1.2)*1.18 – 1.003 ≈ 1%

(the profit is 1% b/c the interest rate in B is 1% below what is consistent with CIP).

c) If CIP were violated, would that be evidence against the EMH?

Yes. If CIP were violated, a riskless profit opportunity would be

being left unexploited, which would be a sign that available information is not being incorporated into market prices.

9a) Why are many emerging market (EM) borrowers facing an

especially hard time meeting their debt payments this year, as the Fed has been aggressively tightening US monetary policy – and how do their problems relate to the “originalsin” of EM borrowing?

The Fed’s tightening has contributed to raising the FX value of the US$. Since many EM borrowers have to pay back their debts in

US$s, while their incomes are in local currency, the rise in the

value of the US$ makes it harder for them to meet their debt payments (b/c their local currency revenue buys them fewer US$s).

The “original sin” of EM borrowing is that many lenders will only accept US$s in payment for lending to EM borrowers, b/c they

think EM lending is too risky – in particular, they are concerned

that the EM currency may fall in value due to inflation. But

denominating EM debt in US$s makes EM borrowers vulnerable to a rise in the value of the US$, increasing the riskiness of EM debt.

b) Suppose the price of a given basket of goods and services is 100 in

Country X (in units of X’s currency) and 200 in Country Y (in units of Y’s currency). The exchange rate is X = 3.5Y. Does this violate PPP?

According to PPP, the FX rate should equalize the price of the same items in the two countries. In this case the items cost twice as much in units of Y’s currency as in units of X’s currency, so Y’s currency

should equal half of X’s (i.e., X = 2Y). The actual FX rate,

X = 3.5Y, thus violates PPP. X is too strong to be consistent with

PPP. Things cost less in Y’s currency than they do in X’s currency.

c) If the Balassa-Samuelson effect is at work, which country is more likely to bean emerging market, with lower productivity?

The Balassa-Samuelson effect is that many non-tradable items (like haircuts) cost more in countries like the US, which have higher

productivity (and wages) in the tradable sectors than EM

countries, b/c if US barbers could only charge as little and earn as little as their counterparts in EMs, no one would become a barber

in the US. So Country Y is likely to be the EM, with lower productivity than X.

10) The yield curve is currently inverted, with the 10-year Treasury rate, for example, below the 3-month T-bill rate, and below the SOFR. a) If spot-futures parity holds, would the spot price of a 10-year

Treasury be above, below, or equal to the price of a six-month futures on that same 10-year Treasury?

F = S (1+r–y), where r = repo rate, y = yield on the 10-year

If the curve is inverted, with 10-year yield is below SOFR (which is the repo rate), r > y, so F > S (the financing cost is greater than the

yield on the bond, so the spot price must be below the futures price, or no one would buy it in the spot market).

b) Why do many interpret the inverted yield curve as a signal that the

US economy is likely to slow sharply, possibly even fall into recession in the future -- and what have those expectations of a slowing economy

likely done to credit default swap (CDS) rates on corporate bonds?

Since LT rates equal the average of current and expected future ST rates plus a TP, if the curve is inverted (i.e. current ST < current

LT), then the avg. of expected future ST rates must be below the

current ST rate (especially if there’s a TP). Expectations that ST rates will fall are often driven by expectations that the economy will slow, possibly even enter recession, prompting the Fed to cut ST rates.

Those expectations have likely caused CDS rates on corporate

bonds to increase. Sellers of CDS agree to pay buyers in the event of a default; increasing prospects of the economy slowing have likely increased the probability of corporate bond defaults, raising the

price demanded by sellers of CDS protection.

c) Why might an inverted yield curve today be a somewhat less reliable signal of impending recession than in past cycles?

If the TP is smaller than in past cycles – b/c of all the LT Treasuries and MBS the Fed has bought -- the yield curve will tend to be flatter than in past cycles, for any given expected future path of ST rates. So the inversion of the yield curve today might be implying a

smaller expected decline in ST rates than a similar-sized inversion would have implied in the past, and hence might be less indicative of a looming recession.

11) a)Why has the Taylor rule been calling for the Fed to hike the funds rate this year?

The Taylor rule calls for raising the funds rate if inflation rises above target – which it has done by a lot this year – and if the

economy is producing above its potential. It is harder to be certain about the latter, but with signs of tightness in the labor market,

and wages and prices accelerating, it seems that the economy is operating above its potential .

b) Briefly explain the Supplementary Leverage Ratio, why it was

imposed on large banks after the financial crisis, and how it differs from the risk-based capital requirement.

The SLR is an additional capital buffer – on top of the risk-weighted capital requirement – that large banks must hold. It is calculated

against all of the bank’s assets – even low-risk ones like Treasuries and reserves at the Fed, which get a weight of zero in the risk-

weighted capital requirement. The SLR was implemented after the financial crisis to further reduce leverage at large banks, and the

moral hazard risks they impose on the financial system and ultimately the taxpayer should they need to be bailed out.

2023-12-29