CCHU9075 Final Essay

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

CCHU9075 Final Essay

Gandhara Buddhist Art: A Cross-Cultural Analysis

Gandhara region, located in northwestern India, has maintained a strong artistic presence as the cradle of the Buddhist high art. The exquisite Gandhara sculptures have been a treasure for Buddhist artistic expressions because of the combination between western sculptural techniques and Asian aesthetics. The artworks have also triggered debate on the origin of the Gandhara art, among which Greek origin and central Indian origin points of view are the most prominent. However, because of the special geographical position, ethnic diversity and prosperous commerce, the formation of the Gandhara art was distinctly influenced by cultural exchange, both from East and West. Neither of the two origin theories could comprehensively summarize the Gandhara aesthetics.

Therefore, this essay will argue for a multi-cultural origin of the Gandhara Buddhist art in an attempt to incorporate and enrich the two origin theories. It will first analyze the Gandhara art with references to its Greek style sculptural characteristics. It will then investigate the Gandhara art’s continuities with the Indian narrative traditions. Lastly, this essay reaches the conclusion that the multi-cultural influence transcended the former styles and molded the uniqueness of the Gandhara art. The Greek origin theory of the Gandhara art was first developed during the colonial era (c. 1849-1947), as shortly after the earliest unearth of the Buddhist relics in 1834, the Gandhara region became a British colony. Under the asymmetric power structure, archaeology and art research was notably monopolized by Western scholars, who examined the Buddhist art with constant references to the legacies of Christianity, Roman art and Greek classicism. The western-oriented mentality of the western scholars was embodied in the naming of the Gandhara art by Foucher, ranging from Classical, Indo-Hellenic to Greco-Buddhist.

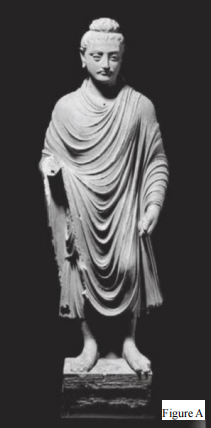

Foucher’s Greek origin theory was echoed by Cunningham, who maintained that the Gandhara Buddhist sculptures were created by the Greeks through the imitation of Apollo’s Colossi. Parallels were drawn between the Gandhara and Greek styles’ sculptural traditions in terms of the smooth folding lines of the garment, the sharp intaglio techniques of the facial features as well as the classical Greek proportion of the statues of standing deities. Ulteriorly, the Greek origin theory was corroborated by later archeological discoveries. In Taxila, stone-relief decorative plates were excavated, which date back to 1B.C., shortly before the birth of the earliest Gandhara Buddhist statue. The functions of the plates were speculated variedly, but most of them had Greek art themes, such as Apollo and Daphne, drunken Dionysus and wine feasts. These discoveries inspired further conjecture that the Greek style plates and relics were the inspirations of the early Gandhara iconography. Artistic legacies from Greece were highlighted in the discourse of the Greek origin theories, while the influence of the Indian local traditions on the Gandhara art was limited to symbols of headgear, accessories and clothing that denote the deities’ identity.

Although the Gandhara Buddhist statues inherit the sculptural features of the west, its postural design, graphical composition and narrative sequence noticeably echo the central Indian traditions. Concurrent with the prosperity of the Kushan Empire (2A.D.), various narrative sculptures of Buddhist stories emerged. They were believed to be the downstream of the Buddhist art on the Bharhut and Sanchi pagodas, the earliest Buddhist iconography in 2B.C. The themes of the stone reliefs include various myths of Shakyamuni’s previous lives as well as the wholesome deeds of the Buddha in this life, which marked the beginning of the Indian narrative art tradition.

Bharhut and Sanchi pagodas could qualify as the lineage of the Gandhara Buddhist art because of their comparable preferences of the figures’ posture. On the left, the three groups of figures (B, C, D) are in a lying posture, with group B as the nirvana scene in Gandhara, group C as Figure D Greek sculpture feast for the dead, and group D being white elephant into the womb on Sanchi pagoda. The Buddha figure in group B follows the standard artistic depiction of nirvana: he lies on his right flank on the platform facing the viewers, with his right arm supporting his head and his left arm placed on the body. The Buddha holds his legs in parallel while slightly bends the upper leg. This posture maintains the folding of the Buddha’s cassock as if it were positioned in his standing posture. This unique design attempts to defuse the dramatic tension of the “death of Shakya” and convey the teaching of impermanence and emptiness.

Western scholars generally regard the Greek sculpture in group C as the prototype of the Gandhara sculpture (Figure B) because of the figures’ similar expression. However, with more careful examination, it could be observed that their similarities, to a large extent, are limited superficially to the graphical layout and the depiction of the smocking. Instead, the expression of the nirvana scene follows a highly stylized tradition: the upper leg’s slight curvature stretches to the front of the Buddha, which is consistent with Queen Mahamaya’s posture. Moreover, in sculptures B and D, the figures are carved in a deliberate leaning gesture, almost forming a right angle (90°) with the bed. However, in the Greek sculpture, the figure is loosely arranged, and the tension of the body is markedly different from the Gandhara expressions. The parallel between the two Buddhist artworks is also rich in spiritual connotations. Through echoing Buddha’s birth and death in similar postures, the artist expresses the Buddha’s transcendence of the karma law and entrance into the realm of eternal life.

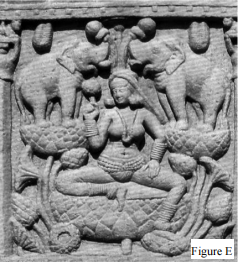

As Akira Miyaji pointed out, centuries ago, when referring to the birth of the Gandhara art, the Greek origin was emphasized; but at present, it is clear that the early Indian art also has a profound influence. In addition to the postural design, the pictorial composition of the Gandhara Buddhist stories is also consistent with the Indian traditions. This sculpture (Figure E) depicts the birth of the Buddha: in the earliest stage when the iconography of the Buddha was forbidden, the Bharhut artists used the symbols of water, lotus and elephant to signify the presence of the Buddha. The two bottles are pouring streams of water, with two elephants standing on the lotus to support the weight of the Buddha. This symmetrical layout strengthens the artistic appeal as well as the spiritual eminence of the Buddha. In the following centuries, the layout gradually became the conventional framework for the depiction of sacred themes in India, including the Gandhara region.

Apart from the postures and pictorial compositions, the Gandhara Buddhist art also

echoes the Indian art in terms of narrative sequence. The pagodas in Sanchi and Bharhut innovated the narrative tradition of the Buddhist scripture by simultaneously displaying the static scenes and dynamic, vivid narrations of the Buddhist stories. They adopt a sub-symmetrical layout: the emphasis of the narration is arranged on one side of the sculpture, while other scenes display their independent spatial-temporal contexts. Through juxtaposing the scenes, the occurrence, development and ending of the storyline intersect as a whole. Take the Buddhist Relics’Distribution among Eight Kings (八王分舍利) as an example (Figure F). The tower far away and the war next to the city wall are arranged within close proximity. The lower part, full of dramatic tension, depicts the invasion towards the city, while the upper part displays the king victoriously riding the elephant and returning with the Buddhist relics, which evidently happens after the war ended.

Similarly, in the Gandhara schist relief of the Buddha’s death (Figure G), the artist adopts a similar narrative pattern to represent the Buddha’s departure in different forms of being. The right side depicts the Buddha surrounded by his disciples, while the left side displays the cremation ceremony. Compared to the disciples expressing various states of grief, the Buddha on the right lies on his shoulder and rests his head in a sense of comfort, marking his achievement of the ultimate spiritual goal, nirvana. The left scene arranges eight devotees surrounding the flame. The number eight is a metaphor, not only for the diverse backgrounds of the Buddhist disciples, but also for how his remains would later be divided into eight portions and buried under the stupas in India, Nepal and Pakistan which witnessed significant events and moments in his life.

Figures F and G embody profound religious connotations through their exquisite craftsmanship. The juxtaposition of the scenes tightens the rhythm of the narration and expresses the implication of time through graphical designs. The comparison between the Gandhara and Sanchi sculptures illustrates the consistency of the Indian narrative tradition: the pictorial construction logic and technique in the Gangetic region were passed on to the Gandhara artists and shaped their fundamental artistic consciousness.

In conclusion, the Gandhara Buddhist art possesses its unique beauty because of both its distinctive Greek-style sculptural techniques and its pictorial designs inherited from central India in terms of postures, symmetrical compositions and narrative sequences. Without a vibrant artistic exchange, Gandhara art could not have intersected the eastern and western aesthetics or obtained its unparalleled artistic achievements. Whether Indian or Greek, the single-origin theories cannot fully conclude the particularity of Gandhara art; but the two theories provide an effective and intriguing framework for the multi-origin analysis of the Gandhara art. The Gandhara Buddhist art is a distinguished product of artistic communications and exchange, and its highly stylized expression is a shared cultural heritage of the entire humanity.

2023-12-11

Gandhara Buddhist Art: A Cross-Cultural Analysis