ECON 200 B: Essay Assignment

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

ECON 200 B: Essay Assignment

Summary of the Issue | Article Link: https://reut.rs/33vqfWv

With COVID-19 cases rising in the weeks leading up to Thanksgiving, many state governors enforced new restrictions on household gathering sizes. This caused many families to rethink and change their Thanksgiving plans in order to limit the spread of COVID-19 and protect their loved ones. These new plans had a tremendous effect on turkey suppliers as more individual families celebrated Thanksgiving at home which caused an increase in demand for smaller turkeys (as opposed to traditionally multiple families gathering and demanding one large turkey). However, because many suppliers had already begun raising turkeys a year in advance in order to produce large turkeys and maximize profits, it was difficult to fulfill customer orders who wanted smaller turkeys. In addition, demand for turkeys overall decreased this year (even with higher demand for smaller turkeys) because many families are struggling with unemployment and some families simply didn’t want the hassle of preparing turkey for only a few guests. Ultimately, retailers adapted to the changing supply and demand by lowering prices of whole turkeys which overall hurt retailers and suppliers’ profits.

Economics Behind the Topic

The turkey industry as a whole exhibits mostly monopolistic competition because there are a few individual firms that have some market power and act as price setter, meaning that they have the ability to raise their prices without losing all their customers. An example in the article is Butterball, which is the largest U.S producer of turkey products. This is because most larger turkey firms sell to retailers, so even if they raise prices, the retailer will still likely purchase from them because the larger turkey firms have the ability to produce more efficiently and fulfil a large order at a lower cost than smaller firms can. However, there are still some small firms that produce turkeys, but they mostly act as price takers, meaning they have little ability to raise their prices otherwise they would lose customers. This is because all firms essentially sell the same product with nothing that dramatically differentiates their turkey from other firms’ turkeys. So, retailers are not willing to pay higher prices for smaller firm’s turkeys when compared to the larger firms’ prices. This causes smaller firms to price turkeys based on larger firms’ prices.

As mentioned in the article, there was an increase in demand for smaller turkeys this year. Typically, in economics, the demand curve would shift to the right (See Demand à Demand’’ in graph 1), increasing the price per small turkey because there is an increased demand.

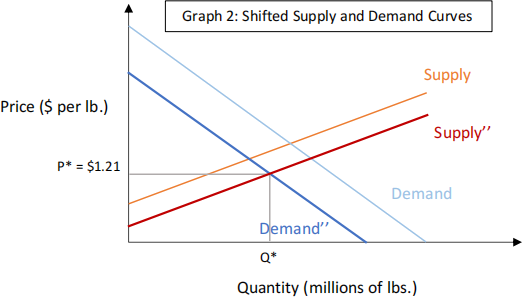

However, since small turkeys are priced and sold the same way as other sized turkeys in terms of pounds, the overall demand for all turkeys (no matter what size) has decreased, according to the article. In addition, the decreased demand is even more magnified by the large number of unemployed families this holiday season as food insecurity has tripled since the pandemic began (according to the U.S. Census Bureau in the article) and some families who rely on others to cook for Thanksgiving also won’t be purchasing turkeys because they simply don’t want the hassle of cooking. (See the demand curve shift left from demand à demand’’ in graph 2 below)

The article also mentioned that suppliers have been preparing for Thanksgiving by producing, slaughtering, and freezing turkeys since the summer before the 2nd wave coronavirus outbreak, so the supply curve also shifts right because the suppliers are willing to sell turkeys at a lower cost in order to sell as many turkeys as possible so they don’t have too much extra supply given the decreased demand (as turkey is perishable). (See the supply curve shift right from supply à supply’’ in graph 2 below)

So, in an effort to maximize profits, retailers have slashed the price of whole turkeys by about 7% to an average price of $1.21 per pound. This increases demand by reaching more consumers with lower willingness-to-pay amounts and also decreases the number of unsold units by pricing at or closer to the equilibrium where supply and demand intersect (which is also more Pareto-efficient).

In the graph below, I am assuming the retailer is pricing at the equilibrium price because since there is much lower demand for turkey this year, I am assuming the retailer wants all consumers to purchase one if are willing to pay (given the right price for the retailer). This is important because turkey is a perishable item, so retailers want to sell as many units as possible to not lose money.

Additionally, both the consumer and producer surplus have decreased as a result of the change in less demand and more supply of turkey. (See surpluses shift from CS&PS à CS’’&PS’’ in graphs 3&4 below)

Turkey would also typically exhibit very inelastic demand during Thanksgiving because people would still buy Turkey even if prices changed as it is a Thanksgiving staple. However, the demand for Turkey is less inelastic this year because many struggling families can’t afford turkey even if the prices are lowered and some families don’t want to bother cooking turkey for only a few guests.

2023-12-04