FNCE 435 - Empirical Finance

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

FNCE 435 - Empirical Finance

Individual Assignment

Underpricing in IPOs: Why Does It Happen?

Abstract

People have been puzzled by the fact that IPOs usually come with very high first-day returns. This pattern, known as underpricing, can be interpreted as IPO firms are leaving money at the table, as they could have charged a higher offering price. We examine some reasons why underpricing does— and should—take place. We find evidence consistent with two explanations. First, underpricing is a way for the firm to compensate investors for revealing their private information, and, second, underpricing is used to entice investors—who fear the information asymmetry intrinsic to the IPO process—to participate in the offering.

1. Introduction

In this study we examine underpricing in initial public offerings (IPOs). An IPO refers to the moment a company goes public. This moment is marked by issuance of public equity, so the IPO is also the first moment the company raises equity in a stock market.

Underpricing denotes the pattern that very often the first day return of the IPO stock is positive and high. That is, if we define the first day return of an IPO company as

=100* ( 1st day close price – offer price)

offer price

it is very common to observe this return to be very high. Let’s start with one single example. When Chipotle went public, its stock was offered at $22 a share (offer_price), but at the end of the very first day it started trading the stock was already priced at $44 (1st day close price). In fact, it started trading at $39.51. Its first day return was thus 100%. Investors that bought the stock during the offering (but prior to the moment it started trading) got a one- day 100% return on their investment! Jay Ritter reports that his is a common pattern amongst IPOs: in a sample of 7,600 US IPOs between 1975 and 2005, the average first day return was 17%.

Notice that when the first day return is high, that can be interpreted as the company is leaving money at the table: the company could be charging more for the stocks being offered. In Chipotle’s case, investors would be happy buying the shares from the initial offering by as much as $44 per share, but the company got only $22 per share. Therefore, we say in this situation that the IPO was underpriced.

Underpricing seems to be so pervasive that it is considered a surprise when it does not happen. The IPO for Facebook is an example. The offer price for Facebook was $38 and it closed at $38.23 at the end of the first trading day, still an underpricing but just under 1%.

There was a huge outcry that somehow the offer price was too high. If we look at the close price, one would argue otherwise, that the offer price in fact was fairly valued.1,2

2. Hypotheses Development

In order to develop our hypothesis, we discuss how the offer price of an IPO is established.3

An important output of the IPO process is the determination of the company value, and thus the price of each stock being offered. To assist the IPO company on this task, the company hires investment banks as advisors. First, the investment banks (or underwriters) analyze the company value and establish a range for the offering price of the firm. For example, for Chipotle, the underwriters described that the offer price would be between $15.50 and $17.50 per share—a initial range of $15.50-$17.50. Second, the underwriters establish a roadshow. Literally they go on the road to meet prospective investors and gauge their reactions about the initial range for the offering price. In the last step, close to the day when the stock starts trading, the underwriters settle on an specific offering price. For our Chipotle case, the offering price was set above the initial range, at $22 per share.

Now we are ready to discuss the hypotheses for why underpricing might happen.

Partial Adjustment

The first hypothesis we will examine is known as the partial adjustment hypothesis. It was first proposed by Benveniste and Spindt (1989). They pointed out that during the roadshow the underwriters collect information about the demand for upcoming IPO, so that the final offering price should thus be related to the demand. If demand is high, underwriters could set a higher offer price. However, investors can know or anticipate that their revealed intentions may be used against them: If they reveal good news about the IPO, it will result in a higher offer price. They may then decline to reveal their excitement about the offering, unless they are offered some reward in return. Underpricing could be such reward. In other words, underpricing is the mechanism by which underwriters entice investors to reveal their private information about the true value of the firm.

The prediction is clear. Underpricing should be higher for the IPOs that gathered positive information from investors during the road show. We can proxy for the level of positive information gathered during the road show by comparing the final price to the initial range—the price adjustment from the road show to final offer. The Chipotle case illustrates this proxy: its final offer price was $22, above the initial range of $15.50-$17.50, suggesting that investors were excited about the offering. Recall also that Chipotle’s IPO faced a high underpricing—a 100% first day return.

To conclude, the partial adjustment hypothesis suggests a positive relationship between the IPO’s price adjustment and its first day return.

Information Asymmetry

Our second hypothesis tests the idea that “underpricing is positively related to the degree of asymmetric information” (Ritter and Welch, 2002). The presence of information asymmetry between informed investors (such as hedge funds, or in general investors that know more about the firm) and retail investors, or between the IPO company (would knows more about itself than investors) and investors could make some investors unwilling to invest in the IPO. These investors would reasonably fear the phenomenon known as winner’s curse: they would be able to buy shares only when the informed agents declined to participate, but that would be the scenario where the offer price would not be attractive to any investor.

This argument predicts that underpricing should be higher the higher the level of information asymmetry for the company going public. Again, underpricing appears as the mechanism to entice the more uninformed investor to participate in the offering.

To conclude, the information asymmetry hypothesis suggests a positive relationship between the level of information asymmetry of the IPO firm and the IPO’s first day return.

3. Data and Methodology

Our approach is to run a regression explaining the IPO’s first day return. If we define RET as the IPO first day return, we run the following regression model,

RETi=β0 + β Xi +εi,

where Xi represents the explanatory variables in the model. Some explanatory variables involve variables used to test the hypotheses above while others are considered simply control variables.

In order to test the partial adjustment hypothesis, we define a variable DELTA_OFFER as the change in offering price from the filing date to the offering date, measured as (OFFER_PRICE–EXPECTED_PRICE)/EXPECTED_PRICE, where EXPECTED_PRICE is the mid-point of the initial filing range.

For the information asymmetry hypothesis, we use the logarithm of the IPO size (measured as total assets), named LTA, as a proxy for information asymmetry.

We have an additional control variable, MARKET_POWER, as a proxy for the quality of the underwriter. The idea is that high-quality underwriters, with more reputation at stake, will make sure that the offering price will be consistent with all information available prior to the offering, thus leading to lower underpricing. MARKET_POWER is defined for each underwriter as the fraction of all IPOs in the period that was handled by that underwriter. The regression model thus becomes:

RETi=β0 + β1 DELTA_OFFERi + β2 LTAi+ β3MARKET_POWERi + εi,

Data on IPOs comprise the period from 1983 through 1987, the same sample period used by Hanley (1993). We complement this data with data on total assets from the Compustat database. Total assets is collected for the same year the IPO takes place.

4. Results

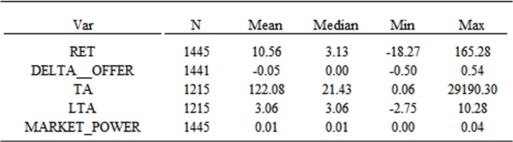

Figure 1 shows some summary statistics on the variables used in the model. There are about 1,445 IPOs in our sample, though not all of them can be used in the regression, as only 1,215 have data available on total assets. Comparing mean and median of total assets illustrates the need to use the logarithm version of total assets, as the original measure of total assets is highly skewed.

Figure 1. Summary statistics

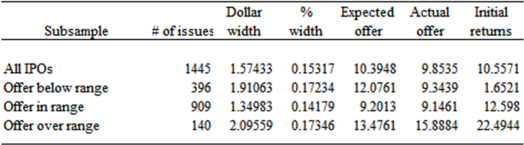

Figure 2 provides a first read on the partial adjustment hypothesis. It shows the averages of the variables from subsamples based on the price adjustment: whether the final price was below the initial range; within the initial range; or above the initial range. The partial adjustment hypothesis is corroborated by these summary statistics: first-day returns are bigger for the sample where the IPO price was adjusted above the initial range set prior to the road show. But, as we always say, this is just univariate statistics, so we turn to the multivariate regressions.

Figure 2. Breaking down the sample based on change in offer price

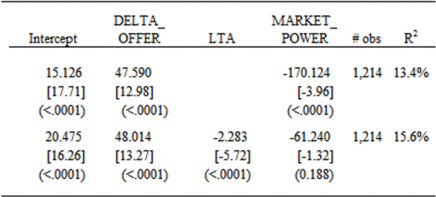

Figure 2 shows the regression results. The first specification mimics the results in Hanley (1993). The coefficient on DELTA_OFFER is significantly positive (t-stat=12.93, p- value<0.0001), rejecting the null of no relationship between change in offer price and underpricing. The coefficient suggests that a 1% increase in the offer price yields an increase of 0.475% in the IPO’s first-day returns. This is evidence consistent with the partial adjustment hypothesis. The model also shows that we underwriters with a larger market share are associated with lower levels of underpricing.

Figure 3. Regression results

The 2nd regression model adds the LTA variable. Its significantly negative coefficient supports the hypothesis that information asymmetry plays a role in underpricing, with bigger firms (which have less information asymmetry) facing lower levels of underpricing. The exact interpretation of the coefficient on LTA is the following: a 1% increase in firm size leads to a decrease of 0.6% in the IPO’s first-day returns. Interestingly, after controlling for LTA, the coefficient on MARKET_POWER becomes insignificant.

5. Conclusion

We examine some possible reasons why underpricing takes place. Using a sample of IPOs from 1983 through 1987, we find evidence to support the partial adjustment and the information asymmetry stories. Specifically, we show that the underpricing increases with the change in offer price and for smaller firms. We leave as an avenue for future analysis whether different proxies for information asymmetry (for example, firm age) would deliver the same inferences.

References

Hanley, 1993. The Underpricing of Initial Public Offerings and the Partial Adjustment Hypothesis. Journal of Financial Economics 34, 231-250.

Ritter, Jay, and Ivo Welch, 2002. A Review of IPO Activity, Pricing, and Allocations. Journal of Finance 57, 1795-1828.

2023-11-24