CSI2107-01: Computer System, Programming Assignment #3

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

The Attack Lab: Understanding Buffer Overflow Bugs

CSI2107-01: Computer System,

Programming Assignment #3

(due on Friday, Nov 24, 2023 by 11:59 pm)

Objectives

The purpose of this assignment is to execute buffer overflow attacks. You will gain firsthand experience with methods used to exploit security weaknesses in operating systems and network servers. Our purpose is to help you learn about the runtime operation of programs and to understand the nature of these security weaknesses so that you can avoid them when you write system code. We

do not condone the use of any other form of attack to gain unauthorized access to any system resources.

Introduction

This assignment involves generating a total of five attacks on two programs having different security vulnerabilities. Outcomes you will gain from this lab include:

• You will learn different ways that attackers can exploit security vulnerabilities when programs do not safeguard themselves well enough against buffer overflows.

• Through this, you will get a better understanding of how to write programs that are more secure, as well as some of the features provided by compilers and operating systems to make programs less vulnerable.

• You will gain a deeper understanding of the stack and parameter-passing mechanisms of x86-64 machine code.

• You will gain a deeper understanding of how x86-64 instructions are encoded.

• You will gain more experience with debugging tools such as GDB and OBJDUMP.

You will want to study Sections 3.10.3 and 3.10.4 of the CS:APP3e book as reference material for this lab.

Handout Instructions

Each student will be assigned a unique target to start working with. Navigate to your home directory inside the class server. You will find a tar file called targetk.tar where k is the unique number associated with your target.

<username>@work space-eber1rx6tf2o-0:~$ ls

targetk.tar ...

Use the following command to retrieve the contents of the tar file.

linux> tar xvf targetk.tar

The files in targetk include:

• README.txt: A file describing the contents of the directory

• c target: An executable program vulnerable to code-injection attacks

• r target: An executable program vulnerable to return-oriented-programming attacks

• cookie.txt: An 8-digit hex code that you will use as a unique identifier in your attacks.

• farm.c: The source code of your target’s “gadget farm,” which you will use in generating return-oriented programming attacks.

• hex2raw: A utility to generate attack strings.

Important Points

Here is a summary of some important rules regarding valid solutions for this lab. These points will not make much sense when you read this document for the first time. They are presented here as a central reference of rules once you get started.

• You must work on the assignment on our class server. Any other domain will not work.

• Your solutions may not use attacks to circumvent the validation code in the programs. Specifically, any address you incorporate into an attack string for use by a ret instruction should be to one of the following destinations:

• The addresses for functions touch1, touch2, or touch3.

• The address of your injected code

• The address of one of your gadgets from the gadget farm.

• You may only construct gadgets from file r target with addresses ranging between those for functions start_farm and end_farm.

Target Programs

Both CTARGET and RTARGET read strings from standard input. They do so with the function getbu f defined below:

1 unsigned getbu f()

2 {

3 char bu f[BUFFER_SIZE];

4 Gets (bu f);

5 return 1;

6 }

The function Gets is similar to the standard library function gets—it reads a string from standard input (terminated by ‘ \n’ or end-of-file) and stores it (along with a null terminator) at the specified destination. In this code, you can see that the destination is an array bu f, declared as having

BUFFER_SIZE bytes. At the time your targets were generated, BUFFER_SIZE was a compile-time constant specific to your version of the programs.

Functions Gets () and gets () have no way to determine whether their destination buffers are large enough to store the string they read. They simply copy sequences of bytes, possibly overrunning the bounds of the storage allocated at the destinations.

If the string typed by the user and read by getbu f is sufficiently short, it is clear that getbu f will return 1, as shown by the following execution examples:

linux> ./ctarget

Cookie: 0x1a7dd803

Type string: Keep it short !

No exploit. Getbu f returned 0x1

Normal return

Typically an error occurs ifyou type a long string:

linux> ./ctarget

Cookie: 0x1a7dd803

Type string: This is not a very interesting string, but it has

the property ...

Ouch !: You caused a segmentation fault !

Better luck next time

(Note that the value of the cookie shown will differ from yours.) Program RTARGET will have the same behavior. As the error message indicates, overrunning the buffer typically causes the program state to be corrupted, leading to a memory access error. Your task is to be more clever with the strings you feed CTARGET and RTARGET so that they do more interesting things. These are called exploit strings.

Both CTARGET and RTARGET take several different command line arguments:

-h: Print list of possible command line arguments

-q: Don’t send results to the grading server

-i FILE: Supply input from a file, rather than from standard input

Your exploit strings will typically contain byte values that do not correspond to the ASCII values for printing characters. The program HEX2RAW will enable you to generate these raw strings. See Appendix A for more information on how to use HEX2RAW.

Important points:

• Your exploit string must not contain byte value 0x0a at any intermediate position, since this is the ASCII code for newline (‘ \n’). When Gets encounters this byte, it will assume you intended to terminate the string.

• HEX2RAW expects two-digit hex values separated by one or more white spaces. So if you want to create a byte with a hex value of 0, you need to write it as 00. To create the word 0x deadbeef you should pass “ef be ad de” to HEX2RAW (note the reversal required for little-endian byte ordering).

When you have correctly solved one of the levels, your target program will automatically send a notification to the grading server. For example:

linux> ./hex2raw < c target.l2.txt | ./ctarget

Cookie: 0x1a7dd803

Type string:Touch2 !: You called touch2(0x1a7dd803)

Valid solution for level 2 with target c target

PASSED: Sent exploit string to server to be validated.

NICE JOB !

The server will test your exploit string to make sure it really works, and it will update the Attacklab scoreboard page indicating that your userid (listed by your target number for anonymity) has completed this phase.

You can view the scoreboard by pointing your Web browser at

http://165.132.118.241:15513/scoreboard

Unlike the Bomb Lab, there is no penalty for making mistakes in this lab. Feel free to fire away at CTARGET and RTARGET with any strings you like.

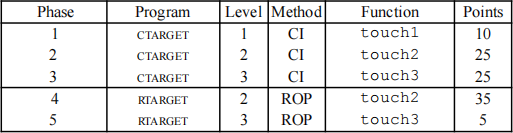

CI: Code injection

ROP: Return-oriented programming

Figure 1: Summary of attack lab phases

Figure 1 summarizes the five phases of the lab. As can be seen, the first three involve code-injection

(CI) attacks on CTARGET, while the last two involve return-oriented-programming (ROP) attacks on RTARGET.

Part I: Code Injection Attacks

For the first three phases, your exploit strings will attack CTARGET. This program is set up in a way that the stack positions will be consistent from one run to the next and so that data on the stack can be treated as executable code. These features make the program vulnerable to attacks where the exploit strings contain the byte encodings of executable code.

CI-Level 1

For Phase 1, you will not inject new code. Instead, your exploit string will redirect the program to execute an existing procedure.

Function getbu f is called within CTARGET by a function test having the following C code:

1 void test()

2 {

3 int val;

4 val = getbu f();

5 printf("No exploit. Getbu f returned 0x%x\n", val);

6 }

When getbu f executes its return statement (line 5 of getbu f), the program ordinarily resumes execution within function test (at line 5 of this function). We want to change this behavior. Within the file c target, there is code for a function touch1 having the following C representation:

1 void touch1()

2 {

3 v level = 1; /* Part of validation protocol */

4 printf("Touch1 !: You called touch1()\n");

5 validate (1);

6 exit(0);

7 }

Your task is to get CTARGET to execute the code for touch1 when getbu f executes its return statement, rather than returning to test. Note that your exploit string may also corrupt parts of the stack not directly related to this stage, but this will not cause a problem, since touch1 causes the program to exit directly.

Some Advice:

• All the information you need to devise your exploit string for this level can be determined by examining a disassembled version of CTARGET. Use obj dump -d to get this dissembled version.

• The idea is to position a byte representation of the starting address for touch1 so that the ret instruction at the end of the code for getbu f will transfer control to touch1.

• Be careful about byte ordering.

• You might want to use GDB to step the program through the last few instructions of getbu f to make sure it is doing the right thing.

• The placement of bu f within the stack frame for getbu f depends on the value of compile-time constant BUFFER_SIZE, as well the allocation strategy used by GCC. You will need to examine the disassembled code to determine its position.

CI-Level 2

Phase 2 involves injecting a small amount of code as part of your exploit string.

Within the file c target there is code for a function touch2 having the following C representation:

1 void touch2(unsigned val)

2 {

3 v level = 2; /* Part of validation protocol */

4 if ( val == cookie) {

5 printf(“Touch2 !: You called touch2(0x%.8x) \n”, val);

6 validate (2);

7 } else {

8 printf(“Misfire: You called touch2(0x%.8x)\n”, val);

9 fail(2);

10 }

11 exit(0);

12 }

Your task is to get CTARGET to execute the code for touch2 rather than returning to test. In this case, however, you must make it appear to touch2 as if you have passed your cookie as its argument.

Some Advice:

• You will want to position a byte representation of the address of your injected code in such a way that ret instruction at the end of the code for getbu f will transfer control to it.

• Recall that the first argument to a function is passed in register %rdi.

• Your injected code should set the register to your cookie, and then use a ret instruction to transfer control to the first instruction in touch2.

• Do not attempt to use jmp or call instructions in your exploit code. The encodings of destination addresses for these instructions are difficult to formulate. Use ret instructions for all transfers of control, even when you are not returning from a call.

• See the discussion in Appendix B on how to use tools to generate the byte-level representations of instruction sequences.

CI-Level 3

Phase 3 also involves a code injection attack, but passing a string as an argument.

Within the file c target there is code for functions hexmatch and touch3 having the following C representations:

1 /* Compare string to hex represent ion of unsigned value */

2 int hexmatch(unsigned val, char *sval)

3 {

4 char cbuf[110];

5 /* Make position of check string unpredictable */

6 char *s = cbuf + random () % 100;

7 sprintf(s, “%.8x”, val);

8 return s trncmp(sval, s, 9) == 0;

9 }

10

11 void touch3(char *sval)

12 {

13 v level = 3; /* Part of validation protocol */

14 if (hexmatch(cookie, sval)) {

15 printf("Touch3 !: You called touch3(\"%s\")\n", sval);

16 validate (3);

17 } else {

18 printf("Misfire: You called touch3(\"%s\")\n", sval);

19 fail(3);

20 }

21 exit(0);

22 }

Your task is to get CTARGET to execute the code for touch3 rather than returning to test. You must make it appear to touch3 as if you have passed a string representation of your cookie as its argument.

Some Advice:

• You will need to include a string representation of your cookie in your exploit string. The string should consist of the eight hexadecimal digits (ordered from most to least significant) without a leading “ 0x.”

• Recall that a string is represented in C as a sequence of bytes followed by a byte with value 0. Type “man ascii” on any Linux machine to see the byte representations of the characters you need.

• Your injected code should set register %rdi to the address of this string.

• When functions hexmatch and strncmp are called, they push data onto the stack, overwriting portions of memory that held the buffer used by getbu f. As a result, you will need to be careful where you place the string representation of your cookie.

Part II: Return-Oriented Programming

Performing code-injection attacks on program RTARGET is much more difficult than it is for CTARGET, because it uses two techniques to thwart such attacks:

• It uses randomization so that the stack positions differ from one run to another. This makes it impossible to determine where your injected code will be located.

• It marks the section of memory holding the stack as nonexecutable, so even ifyou could set the program counter to the start of your injected code, the program would fail with a segmentation fault.

Figure 2: Setting up sequence of gadgets for execution. Byte value 0xc3 encodes the ret instruction. Fortunately, clever people have devised strategies for getting useful things done in a program by executing existing code, rather than injecting new code. The most general form of this is referred to as return-oriented programming (ROP). The strategy with ROP is to identify byte sequences within an existing program that consist of one or more instructions followed by the instruction ret. Such a segment is referred to as a gadget. Figure 2 illustrates how the stack can be set up to execute a sequence of n gadgets. In this figure, the stack contains a sequence of gadget addresses. Each gadget consists of a series of instruction bytes, with the final one being 0xc3, encoding the ret instruction. When the program executes a ret instruction starting with this configuration, it will initiate a chain of gadget executions, with the ret instruction at the end of each gadget causing the program to jump to the beginning of the next.

A gadget can make use of code corresponding to assembly-language statements generated by the compiler, especially ones at the ends of functions. In practice, there may be some useful gadgets of this form, but not enough to implement many important operations. For example, it is highly unlikely that a compiled function would have popq %rdi as its last instruction before ret. Fortunately, with a byte-oriented instruction set, such as x86-64, a gadget can often be found by extracting patterns from other parts of the instruction byte sequence.

For example, one version of rtarget contains code generated for the following C function:

void setval_210(unsigned *p)

{

*p = 3347663060U;

}

The chances of this function being useful for attacking a system seem pretty slim. But, the disassembled machine code for this function shows an interesting byte sequence:

0000000000400f15 <setval 210>:

400f15: c7 07 d4_48 89 c7 movl $0xc78948d4, (%rdi)

400f1b: c3 retq

The byte sequence 48 89 c7 encodes the instruction movq %rax, %rdi. (See Figure 3A for the encodings of useful movq instructions.) This sequence is followed by byte value c3, which encodes the ret instruction. The function starts at address 0x400f15, and the sequence starts on the fourth byte of the function. Thus, this code contains a gadget, having a starting address of 0x400f18, that will copy the 64-bit value in register %rax to register %rdi.

Your code for RTARGET contains a number of functions similar to the setval_210 function shown above in a region we refer to as the gadgetfarm. Your job will be to identify useful gadgets in the gadget farm and use these to perform attacks similar to those you did in Phases 2 and 3.

Important: The gadget farm is demarcated by functions start_farm and end_farm in your copy of rtarget. Do not attempt to construct gadgets from other portions of the program code.

ROP-Level 2

For Phase 4, you will repeat the attack of Phase 2, but do so on program RTARGET using gadgets from your gadget farm. You can construct your solution using gadgets consisting of the following instruction types, and using only the first eight x86-64 registers (%rax–%rdi).

movq : The codes for these are shown in Figure 3A.

popq : The codes for these are shown in Figure 3B.

ret : This instruction is encoded by the single byte 0xc3.

nop : This instruction (pronounced “no op,” which is short for “no operation”) is encoded by the single byte 0x90. Its only effect is to cause the program counter to be incremented by 1.

Some Advice:

• All the gadgets you need can be found in the region of the code for r target demarcated by the functions start_farm and mid_farm.

• You can do this attack with just two gadgets.

• When a gadget uses a popq instruction, it will pop data from the stack. As a result, your exploit string will contain a combination of gadget addresses and data.

ROP-Level 3

Before you take on the Phase 5, pause to consider what you have accomplished so far. In Phases 2 and 3, you caused a program to execute machine code of your own design. If CTARGET had been a network server, you could have injected your own code into a distant machine. In Phase 4, you circumvented two of the main devices modern systems use to thwart buffer overflow attacks. Although you did not inject your own code, you were able inject a type of program that operates by stitching together sequences of existing code. You have also gotten 95/ 100 points for the lab. That’s a good score. If you have other pressing obligations consider stopping right now.

Phase 5 requires you to do an ROP attack on RTARGET to invoke function touch3 with a pointer to a string representation of your cookie. That may not seem significantly more difficult than using an ROP attack to invoke touch2, except that we have made it so. Moreover, Phase 5 counts for only 5 points, which is not a true measure of the effort it will require. Think of it as more an extra credit problem for those who want to go beyond the normal expectations for the course.

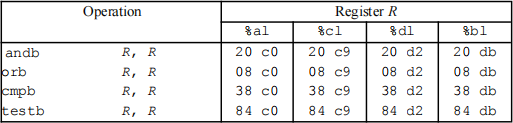

A. Encodings of movq instructions

movq S, D

B. Encodings of popq instructions

C. Encodings of movl instructions

movl S, D

D. Encodings of 2-byte functional nop instructions

Figure 3: Byte encodings of instructions. All values are shown in hexadecimal.

To solve Phase 5, you can use gadgets in the region of the code in r target demarcated by functions start_farm and end_farm. In addition to the gadgets used in Phase 4, this expanded farm includes the encodings of different movl instructions, as shown in Figure 3C. The byte sequences in this part of the farm also contain 2-byte instructions that serve as functional nops, i.e., they do not change any register or memory values. These include instructions, shown in Figure 3D, such as andb %al,%al, that operate on the low-order bytes of some of the registers but do not change their values.

Some Advice:

• You’ll want to review the effect a movl instruction has on the upper 4 bytes of a register, as is described on page 183 of the text.

• The official solution requires eight gadgets (not all of which are unique). Goodluck and have fun!

Hand-in Instructions

You need to submit a PDF report describing how you exploited each target. Your target is connected to the grading server, and is automatically updated upon successful exploitation. Therefore, you do not

need to upload the solution for your target.

Upload the PDF file to LearnUs for submission.

CAUTION: Submit a .pdf file. Any other file formats will not be accepted and graded.

Evaluation

Your score will be calculated out of a maximum of 100 points. The CI target is worth 60 points and the ROP target is worth 40 points. There is an additional 30 points for the report that you submit. Please describe thoroughly how you exploited both targets.

There is a 10% penalty per day ifyou miss the deadline. After 10 days from the deadline, you will not receive any points.

As usual, this is an individual project. You will generate attacks for target programs that are custom generated for you. You are not allowed to discuss the specifics regarding the assignment, and doing so will result in a score of 0.

Tips and Advices

Using HEX2RAW

HEX2RAW takes as input a hex-formatted string. In this format, each byte value is represented by two hex digits. For example, the string “ 012345” could be entered in hex format as “ 30 31 32 33 34 35 00.” (Recall that the ASCII code for decimal digit x is 0x3x, and that the end of a string is indicated by a null byte.)

The hex characters you pass to HEX2RAW should be separated by whitespace (blanks or newlines). We recommend separating different parts of your exploit string with newlines while you’re working on it. HEX2RAW supports C-style block comments, so you can mark off sections of your exploit string. For example:

48 c7 c1 f0 11 40 00 /* mov $0x40011f0,%rcx */

Be sure to leave space around both the starting and ending comment strings (“ /*”, “*/”), so that the comments will be properly ignored.

If you generate a hex-formatted exploit string in the file exploit.txt, you can apply the raw string to CTARGET or RTARGET in several different ways:

1. You can set up a series of pipes to pass the string through HEX2RAW.

linux> cat exploit.txt | ./hex2raw | ./ctarget 2. You can store the raw string in a file and use I/O redirection:

linux> ./hex2raw < exploit.txt > exploit-raw.txt

linux> ./ctarget < exploit-raw.txt

This approach can also be used when running from within GDB:

linux> gdb c target

(gdb) run < exploit-raw.txt

3. You can store the raw string in a file and provide the file name as a command-line argument: linux> ./hex2raw < exploit.txt > exploit-raw.txt

linux> ./ctarget -i exploit-raw.txt

This approach also can be used when running from within GDB.

Generating Byte Codes

Using GCC as an assembler and OBJDUMP as a disassembler makes it convenient to generate the byte codes for instruction sequences. For example, suppose you write a file example.s containing the following assembly code:

# Example of hand-generated assembly code

pushq $0xabcde f # Push value onto stack

addq $17,%rax # Add 17 to %rax

movl %eax,%edx # Copy lower 32 bits to %edx

The code can contain a mixture of instructions and data. Anything to the right of a ‘ #’ character is a comment.

You can now assemble and disassemble this file:

linux> gcc -c example.s

linux> obj dump -d example.o > example.d

The generated file example.d contains the following:

example.o: file format elf64-x86-64

D isassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <.text>:

0: 68 ef c d ab 00 pushq $0xabcde f

5: 48 83 c0 11 add $0x11,%rax

9: 89 c2 mov %eax,%edx

The lines at the bottom show the machine code generated from the assembly language instructions. Each line has a hexadecimal number on the left indicating the instruction’s starting address (starting with 0), while the hex digits after the ‘ : ’ character indicate the byte codes for the instruction. Thus,

we can see that the instruction push $0xABCDEF has hex-formatted byte code 68 ef c d ab 00.

From this file, you can get the byte sequence for the code:

68 ef c d ab 00 48 83 c0 11 89 c2

This string can then be passed through HEX2RAW to generate an input string for the target programs.. Alternatively, you can edit example.d to omit extraneous values and to contain C-style comments for readability, yielding:

68 ef c d ab 00 /* pushq $0xabcde f */

48 83 c0 11 /* add $0x11,%rax */

89 c2 /* mov %eax,%edx */

This is also a valid input you can pass through HEX2RAW before sending to one of the target programs.

2023-11-22

The Attack Lab: Understanding Buffer Overflow Bugs