COMM1110: Assessment 2A Report The Extent of Mortgage Stress in Sydney

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

COMM1110: Assessment 2A Report

The Extent of Mortgage Stress in Sydney

Section 1: Information

What is Mortgage Stress?

Mortgage stress, as defined by the Urban Research Centre is when the cost of housing exceeds 30% of a household’s income (2010). The main stakeholders of mortgage stress involve borrowers, lenders, and financial counsellors. Mortgage stress directly affects borrowers through cases of domestic violence and economic abuse or provoking feelings of failure or shame. Likewise, lenders could experience delayed mortgage payments, thereby delaying business efficiency. Financial counsellors will also be burdened by an excess of cases.

What are the causes of Mortgage Stress?

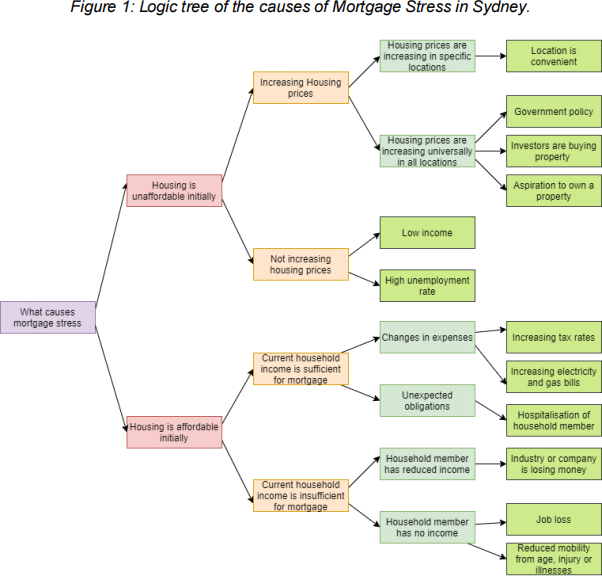

The causes of mortgage stress can be found by deconstructing the reasons for households to spend a large proportion of their income on mortgage repayments (Figure 1).

At the crux of the issue is whether housing is initially unaffordable. This is critical for measuring the extent of mortgage stress as it segregates the problem into the political economy concerns of unaffordable housing and the socioeconomic perspective of affordable housing. Unaffordable housing offers a broader and generalised view of the nested problems in our current economic paradigm such as the “supercharged” housing markets (Konings, et. al, 2020). Conversely, the affordable housing perspective targets the complex financial and social considerations that influence mortgage repayments. The focus will be directed towards the factors that contribute to unaffordable housing. This is due to Sydney’s severely unaffordable housing, where it ranked second worldwide in the 14th Annual Demographia International Survey in 2017 (Lin. D and Geng. Y).

The first branch in unaffordable housing is dependent on the degree to which housing prices are increasing faster than wages. The second observes how disruptions to income such as unemployment and low income, rather than housing prices, affect the borrower’s ability to make mortgage repayments.

Housing prices may be inflated in a specific location or throughout Sydney. Properties in areas such as large urban areas have appreciated faster than wages (Konings et al. 2020) due to the convenience of nearby shops, transport or workplaces. However, with Sydney’s rapid population growth, property values have an upwards trajectory (Lin. D and Geng. Y). Hence, it is also viable to view property inflation as a universal Sydney issue.

Rising property values raises desperation in low-income households who aspire to own a property, prompting households to acquire mortgages they cannot afford. In conjunction, properties are viewed by investors as “wealth-generating assets” (Konings et al. 2020) and used to drive housing prices up. Additionally, government policy such as the government’s proposition to repeal responsible lending laws encourages property purchases, thus generating further concern to the government’s focus on a “mode of governing that prioritises rising asset prices” (Konings et al. 2020).

Criteria for Solutions

A successful solution should reduce the proportion of mortgage stress in Sydney without jeopardising the economy. Housing should be affordable since it is a necessity for all demographics. It should reduce the effects of mortgage stress by offering financial, psychological and domestic support for borrowers and ensure borrowers are fully informed of the nature of their mortgages.

Section 2: Statistical Analysis

Introduction to Variables

A sample of 2000 households who purchased mortgages in Sydney over one month during 2021 was collected to determine the extent of mortgage stress.

Hcost

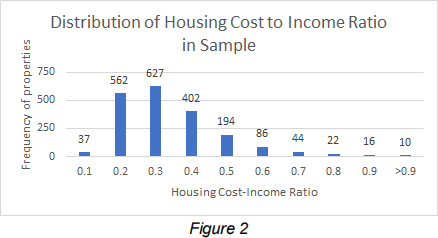

This dependent variable determines the severity of mortgage stress, by using a ratio of weekly mortgage repayments to weekly income.

Figure 2 shows hcost is positively skewed, implying the cost of housing for households in the sample is generally low and safe. It should be noted that the maximum of 0.96 is significantly greater than the mean of 0.294. Large outliers will inflate the mean, meaning the actual hcost may be lower and even safer.

Age

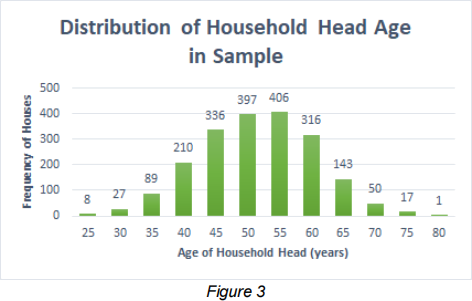

Age is an independent variable that represents the age of the household head in years.

From figure 3, the distribution of age in the sample is almost symmetrical with a mean of 49.458 and a median of 50. Additionally, a range of 54 with a minimum of 22 and a maximum of 76 suggests a balance between youth and elderly people who purchase mortgages.

Comtime

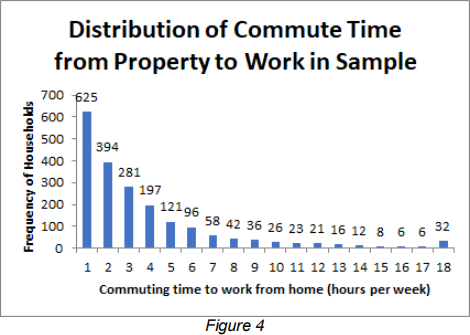

An independent variable defining the weekly commuting time from home to work.

Comtime is positively skewed in figure 4 with a mode of 1, suggesting a large proportion of people purchase properties close to work. A range of 18 hours and a standard deviation of 3.599 hours shows a large spread from the mean.

Lowinc

A dummy variable for income with “1” corresponding to income in the lowest two quintiles and “0” if not.

LowSEIFA

Another dummy variable where “1” represents a property in the lowest two SEIFA quintiles and “0” denotes otherwise.

HCost and Age

There is a low, positive correlation of 0.03. Since there is little correlation between hcost and age in this sample, mortgage stress may be widespread amongst all ages with no clear association between older people and hcost. R2 is 0.00142, shown in Figure 5, which is significantly small. Hence no conclusions can be made from this modelling.

HCost and Comtime

There is a low, negative correlation of -0.0354, suggesting that a higher comtime has a weak association to a lower hcost.

HCost and Income

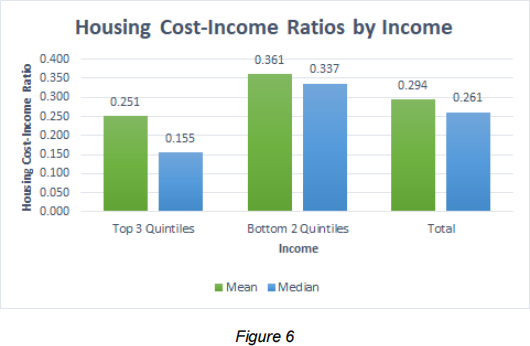

From figure 6, it is clear that mortgage stress impacts people from all income categories. With the highest

mean of 0.361, the bottom 2 quintiles of income are greatly impacted by a higher hcost.

In figure 7, the frequency of households in the top 3 quintiles exceeds the bottom 2 quintiles, potentially due to the greater probability that higher-income households will pass the credit assessment for mortgages. Additionally, a thicker tail for low-income households, despite having a lower frequency than high-income households, implies that low-income households are more at risk of high levels of mortgage stress.

HCost and SEIFA

The correlation between HCost and SEIFA is 0. 1984, demonstrating some positive association. In Figure 8, this association creates a bimodal peak in wealthy areas at 0.2 and 0.3 hcost, centred around the mean of 0.272, showing that a large proportion of wealthy suburbs are likely to have lower mortgage stress.

Overall, high-income areas generally have a safer hcost while lower-income areas have a mean hcost of 0.333, which is higher and less safe.

Summary

There is no clear correlation between hcost and comtime, meaning no conclusion could be made. Furthermore, no clear correlation exists between the housing cost-income ratio and the age of the household head. Rather, the results suggest borrowers range from many ages. Lastly, mortgage stress impacts all income categories and SEIFA areas. However, low-income and low SEIFA households are at more risk for higher stress.

Section 3: Ethics

Assessing the situation

The government’s plan to repeal safe lending laws is an ethical dilemma that places a burden on borrowers to perform their credit assessment when applying for a loan. Ultimately, there will be no legal incentive for banks to lend responsibly and consumers will lose rights to compensations if lenders breach responsible standards. Borrowers will have no protection from making misinformed property purchases. With no option but to rent or mortgage in Sydney, borrowers choose to mortgage out of desperation that housing prices will never decline. Ultimately, more first-home buyers will be subjected to instances of domestic abuse, economic abuse, and psychological stress.

Assumptions and Worldviews

A common assumption is that property prices will never fall. This assumption should be challenged because panic buying properties contributes to inflated housing prices and worsens mortgage stress.

Another risky assumption is that the laws will contribute to property inflation and stimulate economic growth. However, any economic downturn will be significantly magnified as investors cluster to sell their assets when property values decrease, reducing the value of housing for all homeowners.

The laws are distorted by a framing bias that neglects consideration of the borrower’s perspective. For instance, the laws are justified by the government as a means to “urge borrowers to secure timely access to credit (Konings et al. 2020).

Principles, duties, and care needs

Borrowers have rights to housing, basic needs and wellbeing support. As consumers, they have rights to shelter and communication from lenders about their services.

Governments must maintain integrity, transparency and impartiality with the general public. It must provide support services for borrowers and ensure the well-being of financial counsellors. However, an excess of mortgage caseloads will burden financial counsellors, making it also the government’s duty to reduce the number of people requiring such services.

The government must protect borrowers from misinformation, despite increasing the workload for lenders. This may conflict with its duty to ensure the prosperity of the economy. Hence, its interests will often align with lenders, thus worsening the power imbalance between lenders and borrowers.

Governments must not perceive stakeholders from a position of power. Instead, they must implant themselves into the perspective of the stakeholder, learning to develop empathy and compassion.

References

Biddle, N Edwards, B, Gray, M, Sollis, K, 2020, COVID- 19 and mortgage and rental payments: May 2020, Australian National University: Centre for Social Research and Methods

Lin. G, Geng, Y, The Study on Housing Affordability in Sydney. Academic Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (2020) Vol. 3, Issue 7: 32-40.

Konings, M, Adkins, L, Bryant, G, Maalsen, S, Troy, L, 2020, Lock-in and Lock-out: Covid- 19 and the dynamics of the asset economy, Journal of Australian Political Economy, No. 87, pp. 20-47.

Urban Research Centre, 2010. The Experience of Mortgage Distress in Western Sydney, Western Sydney.

2023-06-20