SS5756 Biological Basis of Behavior

Hello, dear friend, you can consult us at any time if you have any questions, add WeChat: daixieit

SS5756 Biological Basis of Behavior

Term Project

Semester B 2022-23

Identifying the endocrine signature of better adjustment using salivary cortisol Background

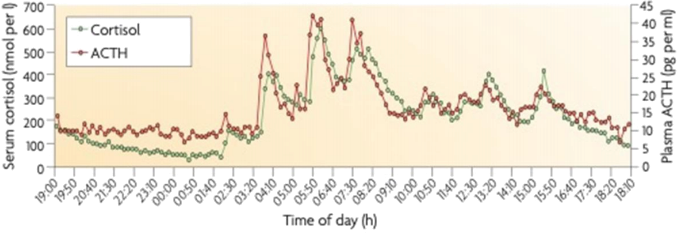

Cortisol plays an important role in helping the organism to cope with stressful situations by mobilizing major energy substrates (Lee, Kim and Choi, 2015). In addition to exposure to stressors, cortisol levels are also determined by signals from the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) via (1) the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis (HPAA) and an autonomic pathway controlling the sensitivity of the adrenal cortex to ACTH (Lightman & Conway-Campbell, 2010). A major challenge of studying cortisol in relation to psychosocial variables is the fact that cortisol is secreted in a pulsatile manner following an ultradian rhythm, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (Henley et al., 2009). Cortisol is secreted in successive pulses that decrease in strength over the course of the day. Higher levels are observed early in the morning; cortisol output gradually decreases over the course of the day until it reaches the nadir or lowest point around midnight. As a result, the circadian rhythm of cortisol assessed using a less intensive protocol will look like

Fig.1. 24h blood sampling profile (every 10 min) of cortisol in 5 healthy participants.

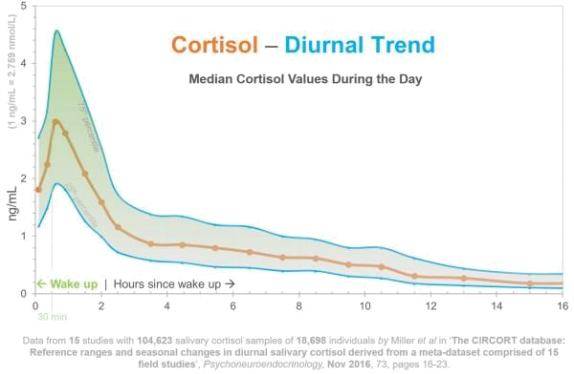

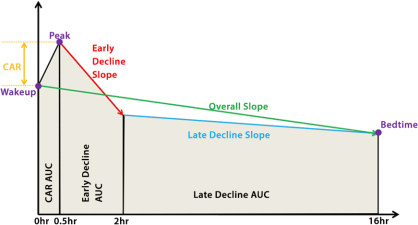

the profile illustrated in Fig.2 (Miller et al., 2016). This diurnal profile has been examined by looking at each major component of the diurnal rhythm separately. The most extensively researched diurnal components include the cortisol awakening response (CAR), overall or diurnal slope (DS) and the diurnal output of cortisol which is equal to the sum of the 3 AUCs in Fig.3 (He et al., 2015). Formulae for computing AUC with reference to ground (AUCG) can be found in Pruessner et al. (2003). There is evidence showing alterations in these components in specific psychiatric conditions: accentuated CAR associated with depression (Bhagwagar et al., 2003), blunted CAR in chronic stress (de Vugt et al., 2005) and PTSD (Labonté et al., 2014), accentuated AUC in depression (Weber et al., 2000), and a flattened DS associated with poor psychological health (Adam et al., 2017). In addition to these diurnal components, another less extensively studied one is the dynamic range of cortisol, which is calculated by the difference between the highest and lowest cortisol levels of a day (e.g., Charles et al., 2020). These researchers have shown that a larger range is associated with lower physiological stress and

Fig.2. Median cortisol values during the day. (retrieved from https://rxhometest.com/article/cortisol-risk-factors)

Fig.3. Major components of the diurnal rhythm of salivary cortisol.

better cognitive functioning in a sample of N = 1001 (ages range from 28-84) in the US.

Although alterations in diurnal cortisol have been reliably demonstrated in different psychiatric conditions, research on characterizing the diurnal rhythm of cortisol in the better adjusted among individuals free of psychiatric problems has lagged behind. Research with Chinese populations along this line of research is so scanty that the drawing of any general conclusions is almost impossible. As both ethnicity (Berger et al., 2017) and culture (Park et al., 2020) have been shown to significantly affect the diurnal cortisol rhythm, cautions should be exerted in extending findings from studies with Western samples to the Chinese people.

In response to the aforementioned findings, this term project is designed to provide students with a chance to explore endocrine markers of better adjustment using a hypothetical dataset provided by the course instructor. In particular, students are required to (1) compute all the cortisol indices as shown in Fig.3 and the dynamic range from the hypothetical dataset, (2) explore the relationship between each of these cortisol parameters and better adjustment by analyzing the differences between 2 groups of individuals in the dataset, and (3) to determine which group is the better adjusted one by referring to results generated in (2).

Report Writing

Students will work in small groups of 6 to 7 to analyze the data set to be provided by the course instructor and write up the findings in a format as specified in Appendix A. In the report, students are required to address issues associated with tasks (1), (2) and (3) mentioned earlier. The length of the report is about 2000 words (a 10% deviation will be tolerated), including tables/figures and references. Each group is required to hand in one report on or before 21 April 2023.

References

Adam, E. K., Quinn, M. E., Tavernier, R., McQuillan, M. T., Dahlke, K. A., and Gilbert, K. E. (2017). Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 83, 25-41.

Berger, M., Leicht, A., Slatcher, A., Kraeuter, A. K., Ketheesan, S., Larkins, S.,… Sarmyai, Z. (2017). Cortisol awakening response and acute stress reactivity in First Nations people. Scientific Reports, 7, 41760.

Bhagwagar, Z., Hafizi, S., and Cowen, P. J. (2003). Increase in concentration of waking salivary cortisol in recovered patients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1890- 1891.

Charles, S. T., Mogle, J., Piazza, J. R., Karlamangla, A., and Almeida, D. M. (2020). Going the distance: The diurnal range of cortisol and its association with cognitive and physiological

functioning. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 112, 104516.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104516

De Vugt, M. E., Nicolson, N. A., Aalten, P., Lousberg, R., Jolle, J., and Verhey, F. R. J. (2005). Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 17, 201-207.

He, Z, Payne, E. K., Mukherjee, B., Lee, S., Smith, J. A., and Ware, E. B., et al. (2015). Association between stress response genes and features of diurnal cortisol curves in the multi- ethnic study of atherosclerosis: A new multi-phenotype approach for gene-based association tests. PLoS ONE, 10(5): e0126637. doi:10. 1371/journal.pone.0126637

Henley, D. E., Leendertz, J. A., Russell, G. M., Wood, S. A., Taheri, S., Woltersdorf, W. W. and Lightman, S. L. (2009). Development of an automated blood sampling system for use in humans. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology,33(3), 199-208.

Labonte, B., Azoulay, N., Turecki, G., and Brunet, A. (2014). Epigenetic modulation of glucocorticoid receptors in posttraumatic stress disorder. Translational Psychiatry, 4, e368; doi: 10. 1038/tp.2- 14.3.

Lee, D. Y., Kim, E., and Choi, M. H. (2015). Technical and clinical aspects of cortisol as a biochemical marker of chronic stress. BMB Reports, 48(4), 209-216.

Lightman, S. L., and Conway-Campbell, B. L. (2010). The crucial role of pulsatile activity ofthe HPA axis for continuous dynamic equilibration. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10 October 2010; doi: 10. 1038/nrn2914.

Miller et al. (2016). The CIRCORT data\base: Reference ranges and seasonal changes in diurnal salivary cortisol derived from a meta-dataset comprised of 15 field studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 73, 16-23.

Park, J., Kitayama, S., Miyamoto, Y., and Coe, C. L. (2020). Feeling bad is not always unhealthy: Culture moderates the link between negative affect and diurnal cortisol profiles. Emotion, 20(5), 721-733.

Pruessner, J. C., Kirschbaum, C., Meinlschmid, G., and Hellhammer, D. H. (2003). To formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28, 916-931.

Weber, B., Lewicka, S., Deuschle, M., Colla, M., Vecsei, P., and Heuser, I. (2000). Increased diurnal plasma concentrations of cortisone in depressed patients. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 85(3), 1133- 1136.

2023-03-06